QUESTO TESTO È STATO SCRITTO NELLA PRIMAVERA DEL 2022, INIZIALMENTE COME PROFILO SU SILVIA CALDERONI E SUCCESSIVAMENTE INTEGRATO CON UNA NOTA SULLA COLLABORAZIONE ARTISTICA CON ILENIA CALEO, CHE IN QUEI MESI COMINCIAVA A DARE I SUOI PRIMI FRUTTI AL CASTELLO DI RIVOLI. NEL FRATTEMPO, LE DUE AUTRICI E PERFORMER HANNO PORTATO AVANTI LA LORO RICERCA, DI CUI HANNO PRESENTATO IMPORTANTI TAPPE AL TENAX THEATRE / FABBRICA EUROPA (FIRENZE, OTTOBRE 2022), AL KAMPNAGEL (AMBURGO, GENNAIO 2023), AL TEATROLTRE (PESARO, FEBBRAIO 2023).

La ricerca di Silvia Calderoni è impossibile da confinare all’interno di un solo linguaggio. Sicuramente nasce dal teatro di ricerca come dimensione in cui esprimere una serie di istanze per cui la società non ha ancora alfabeti disponibili. Il corpo è la materia prima e viva attraverso cui instaurare un tacito patto tra sé e il pubblico, è lo strumento attraverso cui travalicare i confini della scena tradizionalmente intesa per toccare mondi limitrofi, come l’arte, la moda e il cinema.

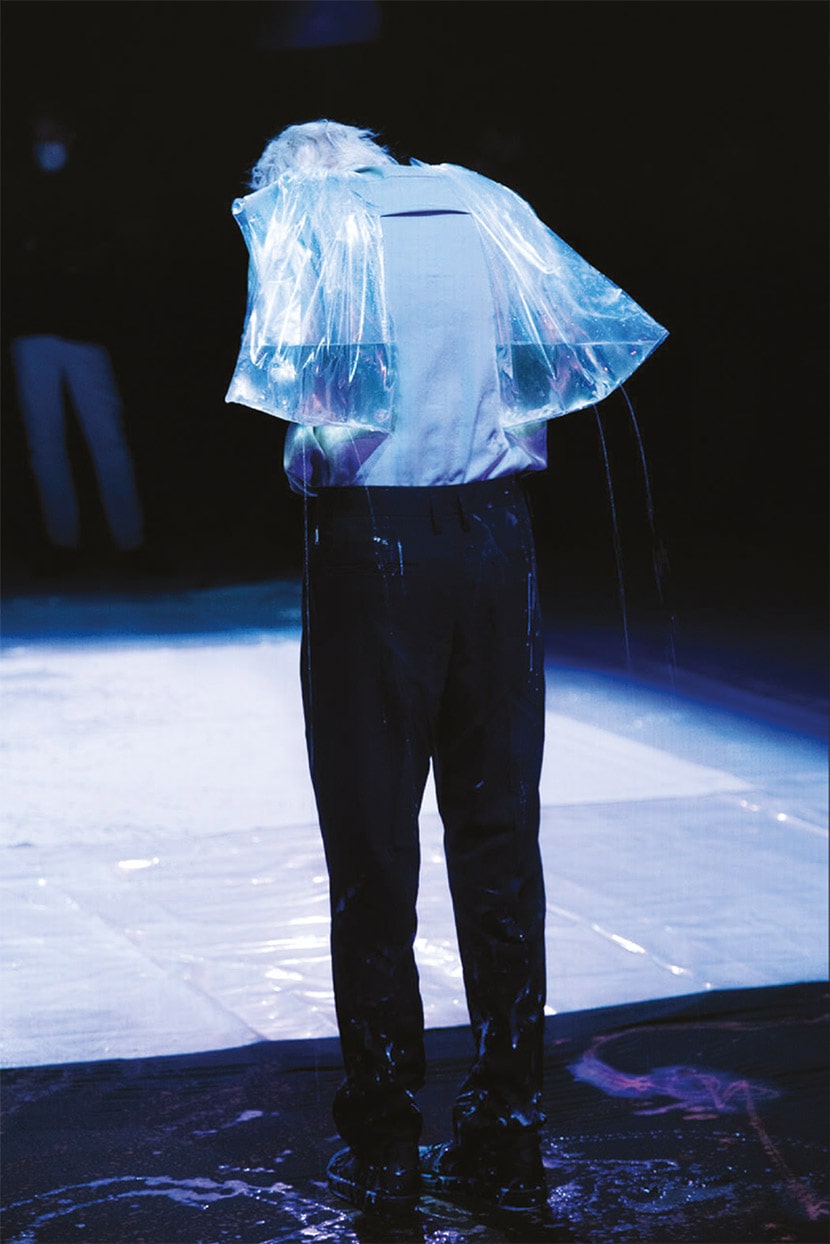

Il reenactment di Covered in Detergent on Stage, Bathing in Water (1964) di Nam June Paik, presentato a novembre 2021 al Pirelli HangarBicocca,1 è una collaborazione tra Silvia Calderoni e Ilenia Caleo che colpisce subito per la dimensione visuale e pittorica.

La proposta del coreografo Alessandro Sciarroni e del curatore Davide Quadrio era di partire da un materiale storico e, seguendo le modalità di Fluxus, rimetterlo in circolo, riabitarlo.

Le performer indagano la relazione tra corpo e materia, immediata nell’opera di Paik, per declinarla sulle visioni proprie del teatro e del tema del progetto complessivo: Mare Nostrum.

L’azione si basa su una partitura fisica, attraverso i due sacchetti che Calderoni tiene in mano sgocciolano a terra sostanze chimiche tossiche: candeggina e vernice luminescente che sostituiscono i pigmenti della versione di Paik degli anni Sessanta. La scrittura coreografica è minata dall’imprevedibilità con cui queste sostanze si distribuiscono sui tessuti predisposti a terra.2

La possibilità di visualizzare la traccia dell’azione performativa è concessa in un secondo momento, si crea una dilazione tra l’espressività del corpo e il modo in cui affiorano a terra i segni “pittorici”. Ci si trova di fronte al risultato di un passato appena sfuggito, perso alla vista ma ancora vivido nella memoria. Dalla prospettiva di Calderoni – e del teatro – l’azione è orientata a un qualcosa che si riallaccia al futuro, una relazione tra presente e futuro che disattende le previsioni, quindi il controllo. La candeggina versata su un tessuto scuro lascia affiorare l’immagine lentamente e autonomamente. La vernice luminescente bianca su un tessuto bianco solo in un secondo momento è irradiata da Ilenia Caleo con una piccola luce di Wood. I segni dell’azione terminata da poco si rivelano per piccole porzioni.

L’esito dell’azione nel teatro è percepito come un avanzo, un guscio che rimane, ma in questo caso i tessuti rimasti hanno una forza intrinseca anche una volta che il corpo non c’è più.

Il cambio di contesto (il museo) e di pubblico (quello dell’arte) che guarda all’azione/oggetto in questione ne riconfigura il significato. Ciò che permane dal punto di vista delle arti visive è oggetto, o meglio, “impronta” che conserva al suo interno l’assenza del corpo e la memoria del gesto che l’ha generata. Il residuo è la pelle di un serpente attraverso cui si riattualizza il momento generativo della trasformazione, è fine e sorgente al tempo stesso di un costante reenactment.

Lo sguardo dell’arte è melanconico, riattiva ma non dimentica quella prima volta in cui la creazione ha preso forma. Nel teatro accade qualcosa di molto diverso. Silvia Calderoni lo descrive come un principio d’eclissi, due pianeti si allineano e succede qualcosa, in quel caso i pianeti sono il pubblico e lo spettacolo. Finisce l’allineamento e del teatro non resta nulla, mentre un’opera d’arte continua a esistere come presenza. Nel teatro l’aura che anima gli oggetti sul palco si dissolve appena si chiude metaforicamente il sipario. Nelle arti visive la dimensione processuale è spesso funzionale alla strutturazione di senso di un oggetto creato dall’artista nell’intimità del suo studio, pensiamo alle foto di Ugo Mulas a Lucio Fontana mentre taglia le sue tele.

Questo sconfinamento tra mondi, tra linguaggi, cambia lo sguardo e quindi i vertici della relazione che si genera tra osservatore e osservato. Cambia il modo di guardare a ciò che sta accadendo e ai resti lasciati dietro di sé, ai passaggi di stato che connotano l’identità di corpi, gesti e oggetti.

Il corpo è materia prima anche nella moda, è presenza ancora una volta imprescindibile perché l’abito è uno dei modi in cui i corpi possono abitare il mondo attraverso molteplici forme di autorappresentazione. Dal 2017 Silvia Calderoni collabora con Gucci invitata dal direttore creativo Alessandro Michele, interessato fin da subito a riconfigurare l’identità visiva e concettuale della casa di moda. Prende forma così un terreno fertile per contaminazioni reciproche. «Alessandro Michele è un visionario – spiega l’artista –, il principio che regola la sua ricerca non è vestire un corpo singolo ma vestire una società, quindi non è mai un abito ma una moltitudine di abiti. Il suo è un disegno sempre più largo rispetto all’individuo, come se nella foto che ha in mente ci fossero sempre tantissime persone». Il pensiero performativo e collettivo e la preponderante componente visuale riportano il linguaggio della moda a una dimensione sperimentale e artistica. Questa visione si ritrova anche nella collaborazione, vera e propria triangolazione, tra Michele, Calderoni e Gus Van Sant. Le immagini oniriche del regista, l’abilità di maneggiare l’inesplorato del direttore creativo e la capacità di essere materia viva dell’attrice e performer si alimentano a vicenda. Il risultato è un panorama su un mondo polifonico di incontri umani regolati da grande libertà, una dimensione di ricerca in cui mettersi alla prova e dove può accadere l’inaspettato.

Anche quando si confronta con il cinema Silvia Calderoni intreccia linguaggi e porta lo sguardo dello spettatore su altre prospettive. Il rapporto con la cinepresa è molto diverso da quello che si crea quando un corpo è davanti ad altri corpi nel teatro, o nel museo. Nel film Non mi uccidere di Andrea De Sica, Calderoni lavora su una recitazione che dissimula il personaggio, e in qualche modo lo incarna con un metodo che lei definisce strasberghiano. Attinge a un bagaglio personale per far parlare Sara, il personaggio del film, tramite il suo corpo e la sua voce. Nel film Sara aiuta la protagonista ad accettare il passaggio alla sua nuova condizione di zombie e le fa vedere come lei stessa si nutra solo di uomini violenti. Non è la prima volta che i ruoli che Silvia Calderoni porta sul grande schermo trattino temi come la violenza di genere, sia fisica che sociale. Nel 2017, nel film Amori che non sanno stare al mondo di Francesca Comencini, il suo personaggio tiene una lezione sul sistema “eterocapitalista” – ispirata ai testi di Paul B. Preciado – in cui è teorizzata la posizione sociale e anagrafica delle donne attraverso le regole del mercato sessuale. La regia in questo caso sceglie un bianco e nero per questa scena, delineando una separazione netta dell’episodio dal resto della narrazione che evoca una messa in scena teatrale.

Nel cinema il patto tra spettacolo e spettatore è sovvertito dalla finzione: il modo in cui lo sguardo è indirizzato dalla cinepresa, dal montaggio, o illuso dagli effetti speciali, catapulta lo spettatore in un mondo dove smette di sentire se stesso ed entra in quelle storie. Il teatro invece, con il corpo vivo dell’attore, entra nello spazio reale e chiama attivamente a partecipare.

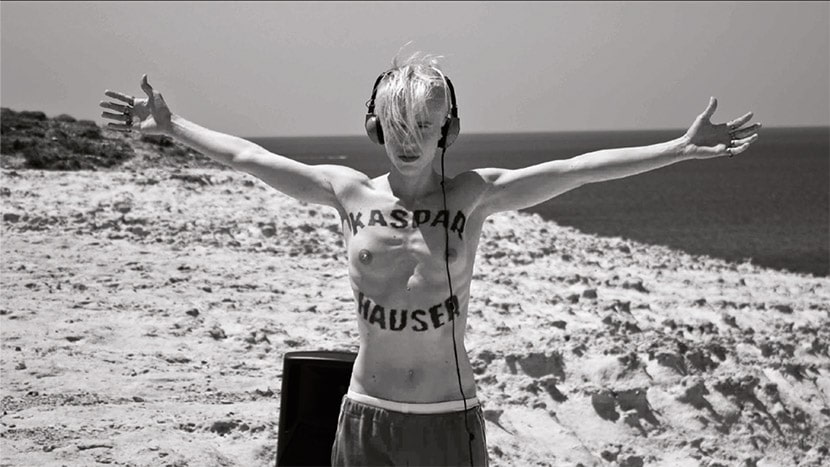

Nel 2012 Silvia Calderoni è Kaspar Hauser nel film di Davide Manuli, La leggenda di Kaspar Hauser. Il protagonista è una creatura fuori contesto, un folle, un profeta o un impostore, che ribadisce costantemente chi è – «Io sono Kaspar Hauser» ripete a mo’ di mantra – senza mai prendere realmente parte alla vita della comunità in cui si trova, senza svolgere una effettiva funzione nello scenario di per sé surreale del film. Le sue frasi brevi ed enigmatiche, nella loro semplicità, sono intese ogni volta in senso diverso dai personaggi del film, come oracoli o menzogne, profezie o nonsense.

La fisicità e la recitazione di Silvia Calderoni destrutturano la finzione, il suo corpo non dissimula il suo peso o la sua gestualità a favore di camera come accade solitamente nel cinema, introducendo una forte componente di verità, radicale ma non ostentata, comunque disorientante.

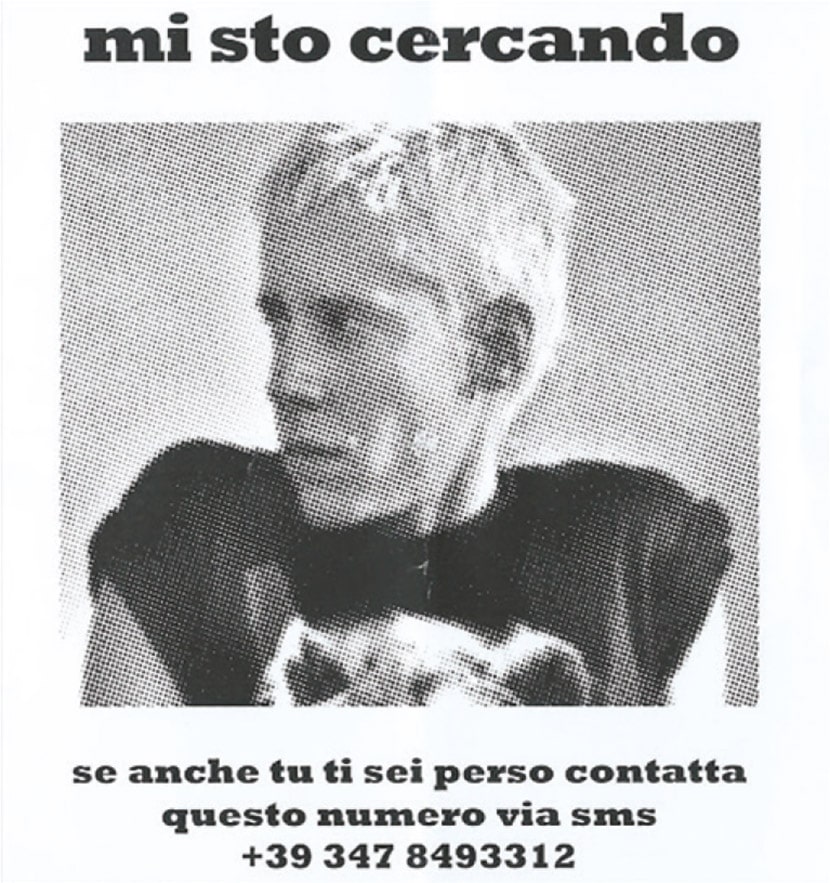

Nel 2007, a Santarcangelo, l’artista distribuiva ai passanti dei volantini con la scritta «mi sto cercando», la sua foto e un numero di telefono da contattare. Era il primo movimento di X(ics) Racconti crudeli della giovinezza di Motus, un’azione teatrale che è anche una posizione artistica ed esistenziale portata avanti attraverso il teatro e i ripetuti sconfinamenti tra cinema, moda e arte. Inseguire nuovi linguaggi per cercarsi, per dare corpo ai passaggi di stato dell’identità, per cambiare prospettive: guardare all’arte visiva come un attimo irripetibile ma sempre rinnovabile, al cinema come un luogo di sperimentazione corporea, guardare alla moda come grande dipinto di gruppo o al teatro come a un tacito accordo tra corpi e azioni.

Silvia Calderoni e Ilenia Caleo. Il corpo è materia prima anche quando non c’è

Nell’ultimo progetto Pick Pocket Paradise (Il Paradiso dei borseggiatori) (2022), realizzato da Silvia Calderoni con l’attivista e ricercatrice Ilenia Caleo – compagna nell’arte e nella vita –, si esperisce una dimensione corporea nuova, le performer non ci sono, a differenza del reenacting dell’opera di Nam June Paik: il vero protagonista è il visitatore, disorientato dall’installazione. Sia che si conosca il lavoro performativo di Silvia Calderoni e Ilenia Caleo sia che si entri nell’installazione senza aver mai incontrato le due autrici, ci si trova immersi in un’atmosfera trasognata, dove l’odore pungente delle ortiche insieme a quello del terriccio sono qualcosa di inaspettato nelle sale per le quali l’opera è stata ideata, al piano nobile del Castello di Rivoli.3 L’installazione è urticante, non solo dal punto di vista letterale – la radice etimologica delle piante che la compongono –, ma anche concettualmente ed esteticamente.

Il progetto è una riflessione sul cruising, una pratica divenuta comune negli Stati Uniti a cavallo tra anni Settanta e Ottanta, un’epoca in cui la cultura occidentale oscillava tra gli estremi del conservatorismo reganiano da un lato e dall’altro cominciavano a prendere coscienza e quindi forma politica movimenti per la tutela dei diritti queer. Si trattava di un momento storico in cui, nonostante le limitazioni imposte dalla società, le forme di eversione rispetto alle consuetudini borghesi individuavano spazi, seppur confinati, dove manifestarsi. Pratiche come il cruising trovavano un loro “luogo” per esprimersi nei Piers, grandi moli/palafitte lungo il fiume Hudson. Queste strutture urbanistiche erano all’epoca, prima della privatizzazione, una sorta di porto franco, un terreno fertile per eccedere il conforme in termini di sperimentazione sia politica, sessuale e sociale che artistica – tra i frequentatori della comunità c’erano infatti David Wojnarowicz, Keith Haring e Gordon Matta-Clark tra gli altri. Risulta quindi sorprendente, oggi, riscoprire attraverso la ricerca su archivi storici un mondo non tanto lontano nel tempo in cui la ricerca artistica andava a braccetto con comportamenti sessuali non conformi, in cui il pensiero trovava, in una dimensione fuori dai circuiti mainstream, uno spazio affettivo ricco di «potenzialità di futuro», come lo descrivono Calderoni e Caleo.

Ma Pick Pocket Paradise è urticante anche dal punto di vista estetico. Il visitatore, attore e spettatore al tempo stesso, è “costretto” a camminare su una passerella che forma una sorta di ansa all’interno della stanza e ad avvicinarsi alla parete di fondo su cui si trova una carta da parati che ripete un motivo apparentemente decorativo.

Il pattern è composto da un’ordinata geometria, fredda e digitale che riproduce in un loop visivo un dettaglio della fotografia En Masse, Sunners Seen from Pier 45 (1982) di Frank Hallam. Ciò che lo scatto cattura – e l’occhio del visitatore comprende solo avvicinandosi – è una scena che di primo acchito sembra rimandare all’iconografia “classica” delle bagnanti, ma addentrandosi nell’installazione risulta evidente che il contesto cronologico e geografico non è più quello mitologico, bensì una scena di vita vera della comunità queer americana all’inizio degli anni Ottanta. Si riscopre la prurigine che dovette provare la giuria accademica del Salon nel 1863 quando rifiutò Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe di Manet. D’altra parte le scene di corpi virili avvinghiati non sono mancate nell’arte, anche andando più indietro nel tempo, ma hanno sempre dovuto trovare una loro legittimazione attraverso la narrazione mitologica, come La zuffa degli dei marini del Mantegna.

Questa lieve sensazione di fastidio epidermico non troppo dolorosa non inficia davvero il normale svolgimento delle attività della fruizione complessiva della mostra in cui è inserita l’installazione – ma si fa sentire nel tempo. In biologia, le cellule urticanti sono dotate di piccole spine che quando vengono toccate rilasciano una sostanza che allerta i ricettori neuronali, sono un organo di difesa che può inibire i predatori dall’avvicinarsi alla pianta ma anche un trattamento che ha molti benefici per il corpo. Nel caso di Pick Pocket Paradise, anche quello sociale.

Arte e Critica, n. 97-98, primavera – estate 2023, pp. 24-30.

1. L’opera fa parte del progetto “Flu水o”, a cura di Davide Quadrio, da un’idea di Luciana Galliano, sotto la direzione artistica di Alessandro Sciarroni, che è stato presentato al Pirelli HangarBicocca il 25 e 26 novembre 2021.

2. Anche i tessuti sono una variazione dell’opera di Nam June Paik che nella versione storica aveva adottato delle grandi carte.

3. Nell’ambito della mostra Espressioni con frazioni, a cura di Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, Marcella Beccaria, Marianna Vecellio e Fabio Cafagna con il coordinamento curatoriale di Anna Musini, Castello di Rivoli, Torino, 24 aprile – 25 settembre 2022.

SOME REFLECTIONS ON SILVIA CALDERONI’S PRACTICES. FLOWING BETWEEN DIFFERENT LANGUAGES TO GIVE SUBSTANCE TO THE TRANSITIONS OF STATE OF IDENTITY

THIS TEXT WAS WRITTEN IN THE SPRING OF 2022, INITIALLY AS A PROFILE OF SILVIA CALDERONI AND LATER COMPLEMENTED WITH A NOTE ON THE ARTISTIC COLLABORATION WITH ILENIA CALEO, WHICH IN THOSE MONTHS WAS BEGINNING TO BEAR FRUIT AT CASTELLO DI RIVOLI. IN THE MEANTIME, THE TWO AUTHORS AND PERFORMERS HAVE CONTINUED THEIR RESEARCH, THE MOST IMPORTANT STAGES OF WHICH THEY PRESENTED AT TENAX THEATRE / FABBRICA EUROPA (FLORENCE, OCTOBER 2022), KAMPNAGEL (HAMBURG, JANUARY 2023), AND TEATROLTRE (PESARO, FEBRUARY 2023).

It is impossible to confine Silvia Calderoni’s research within a single language. It certainly stems from research theatre as a dimension in which to express a series of issues for which society does not yet have alphabets available. The body is the raw and living material through which a tacit pact between the self and the audience is established, it is the instrument through which the boundaries of the traditionally understood scene are transcended to touch neighbouring worlds, such as art, fashion and cinema.

The reenactment of Covered in Detergent on Stage, Bathing in Water (1964) by Nam June Paik, presented in November 2021 at Pirelli HangarBicocca, is a collaboration between Silvia Calderoni and Ilenia Caleo that is immediately striking in its visual and pictorial dimensions.1

The proposal of the choreographer Alessandro Sciarroni and the curator Davide Quadrio was to start from a historical material and, following Fluxus modalities, put it back into circulation, re-inhabit it.

The performers explore the relationship between body and material, which is immediate in Paik’s work, in order to decline it according to the visions proper to theatre and to the overall project: Mare Nostrum.

The action is based on the physical score, through the two bags Calderoni holds toxic chemicals drip onto the ground: bleach and luminescent paint that replace the pigments of Paik’s 1960s version. The choreographic writing is undermined by the unpredictability with which these substances are distributed on the fabrics arranged on the ground.2

The possibility of visualizing the trace of the performative action is granted later, a dilation is created between the expressiveness of the body and the way the ‘pictorial’ signs emerge on the ground. One is confronted with the result of a just vanished past, lost to view but still vivid in memory. From the perspective of Calderoni – and of theatre – the action is oriented towards something that makes reference to the future, a relationship between present and future that disregards prediction, hence control. Bleach poured on a black fabric allows the image to emerge slowly and independently. White luminescent paint on a white fabric is only later irradiated by Ilenia Caleo with a small Wood’s lamp. The signs of the recently finished action are revealed in small portions.

The result of the action in the theatre is perceived as a leftover, a shell that remains, but in this case the remaining fabrics have an intrinsic strength even once the body is no longer there.

The change of context (museum) and audience (that of art) looking at the action/object in question reconfigures its meaning. What remains from the perspective of the visual arts is an object, or rather an ‘imprint’ that preserves within it the absence of the body and the memory of the gesture that generated it. The residue is the skin of a snake through which the generative moment of transformation is reorganized, it is at the same time the end and the source of a constant reenactment.

The gaze of art is melancholic, it reactivates but does not forget that first time when creation took shape. Something very different happens in the theatre. Silvia Calderoni describes it as the beginning of an eclipse, two planets align and something happens, in that case the planets are the audience and the performance. The alignment ends and nothing remains of the theatre, while a work of art continues to exist as a presence. In the theatre, the aura that animates the objects on stage dissolves as soon as the curtain metaphorically closes. In the visual arts, the process dimension is often functional to the structuring of meaning of an object created by the artist in the intimacy of his studio, think of Ugo Mulas’ photographs of Lucio Fontana while he is cutting into his canvases.

This crossover between worlds, between languages, changes the gaze and thus the vertices of the relationship generated between observer and observed. It changes the way of looking at what is happening and at the remains left behind, at the passages of state that connote the identity of bodies, gestures and objects.

The body is also raw material in fashion, it is once again an unavoidable presence because clothing is one of the ways in which bodies can inhabit the world through multiple forms of self-representation. Since 2017 Silvia Calderoni has been collaborating with Gucci, invited by creative director Alessandro Michele, who was immediately interested in reconfiguring the visual and conceptual identity of the fashion house. Thus a fertile ground for mutual contaminations takes shape. “Alessandro Michele is a visionary,” the artist explains, “the principle that governs his research is not to dress a single body but to dress a society, so it is never one dress but a multitude of dresses. His design is always broader than the individual, as if there were always so many people in the picture he has in mind.”

The performative and collective thinking and the preponderant visual component bring the language of fashion back to an experimental and artistic dimension. This vision is also found in the collaboration, a real triangulation, between Michele, Calderoni and Gus Van Sant. The director’s dreamlike images, the creative director’s ability to handle the unexplored, and the actress and performer’s ability to be living matter feed each other. The result is a panorama on a polyphonic world of human encounters governed by a great freedom, a dimension of research in which to test oneself and where the unexpected can occur.

Even when dealing with cinema, Silvia Calderoni interweaves languages and takes the viewer’s gaze to other perspectives. The relationship with the camera is very different from the one created when a body is in front of other bodies in the theatre, or in the museum. In the film Non mi uccidere [Don’t Kill Me] by Andrea De Sica, Calderoni works on a recitation that dissimulates the character, and somehow embodies him with a method that she calls Strasbergian. She draws on personal experience to make Sara, the film’s character, speak through her body and her soul. In the film, Sara helps the protagonist accept the transition to her new condition as a zombie and shows her how she herself only feeds on violent men. This is not the first time that the roles that Silvia Calderoni brings to the big screen deal with themes such as gender-based violence, both physical and social. In 2017, in the film Amori che non sanno stare al mondo [Stories of Love That Cannot Belong to This World] by Francesca Comencini, her character gives a lecture on the ‘hetero-capitalist’ system – inspired by the texts of Paul B.Preciado – in which the socio-anagraphic position of women is theorized through the rules of the sexual market. The director in this case chooses black and white for this scene, delineating a clear separation of the episode from the rest of the narrative that evokes a theatrical staging.

In cinema, the pact between spectacle and spectator is subverted by fiction: the way in which the gaze is directed by the camera, by editing, or deceived by special effects, catapults the spectators into a world where they stop feeling themselves and enter those stories. Theatre, on the other hand, with the actor’s living body, enters the real space and actively calls for participation.

In 2012 Silvia Calderoni is Kaspar Hauser in Davide Manuli’s film, La leggenda di Kaspar Hauser [The Legend of Kaspar Hauser]. The protagonist is an out-of-context creature, a madman, a prophet or an impostor, who constantly restates who he is – “I am Kaspar Hauser” he repeats like a mantra – without ever really taking part in the life of the community in which he finds himself, without playing an actual function in the film’s surreal scenario. His short and enigmatic phrases, in their simplicity, are each time understood in a different sense by the film’s characters, as oracles or lies, prophecies or nonsense.

Silvia Calderoni’s physicality and acting deconstruct fiction, her body does not dissimulate her weight or her gestures in favour of the camera as it usually happens in cinema, introducing a strong component of truth, radical but not ostentatious, nevertheless disorienting.

In 2007, in Santarcangelo, the artist distributed leaflets to passer-by with the words “I am looking for me,” her photograph and a telephone number to contact. It was the first movement of X(ics) Racconti crudeli della giovinezza [X(ics) Cruel Tales of Youth] by Motus, a theatrical action that is also an artistic and existential stance pursued through theatre and repeated crossovers between cinema, fashion and art.

Pursuing new languages in order to search for oneself, to give substance to the transitions of state of identity, to change perspectives: looking at visual art as an unrepeatable but always renewable moment, at cinema as a place of bodily experimentation, looking at fashion as a large group painting or at theatre as a tacit agreement between bodies and actions.

Silvia Calderoni and Ilenia Caleo. The body is raw material even when it is not there

In the latest project Pick Pocket Paradise (Il Paradiso dei borseggiatori) (2022), realised by Silvia Calderoni together with the activist and researcher Ilenia Caleo – partner in art and life – a new bodily dimension is experienced, performers are not there, unlike the reenactment of Nam June Paik’s work: the real protagonist is the visitor, disoriented by the installation. Whether one is familiar with the performance work of Silvia Calderoni and Ilenia Caleo or enters the installation without ever having met the two authors, one finds oneself immersed in a dreamy atmosphere, where the pungent odour of nettles together with that of soil are something unexpected in the rooms for which the work was conceived, on the piano nobile of the Castello di Rivoli.3 The installation is stinging, not only from a literal point of view – the etymological root of the plants that compose it – but also conceptually and aesthetically.

The project is a reflection on cruising, a practice that became commonplace in the United States between the end of 1970s and the beginning of the 1980s, a time when Western culture was oscillating between the extremes of Reaganist conservatism on the one hand and queer rights movements that were beginning to gain awareness and thus political form on the other. That was a historical moment in which, despite the limitations imposed by society, forms of subversion of bourgeois customs found spaces, albeit confined, where they could become manifest.

Practices such as cruising found their ‘place’ to express themselves in the Piers, large piers/pilings along the Hudson River. These urban structures were at the time, before privatisation, a sort of free port, a fertile ground for exceeding conformity in terms of political, sexual and social as well as artistic experimentation – the community’s regular visitors included David Wojnarowicz, Keith Haring and Gordon Matta-Clark among others. It is therefore surprising, today, to rediscover through research in historical archives a world not so distant in time where artistic research went hand in hand with nonconforming sexual behaviours, where thought found, in a dimension outside the mainstream circuits, an affective space rich in “potential of futures,” as Calderoni and Caleo describe it.

But Pick Pocket Paradise is also stinging from an aesthetic point of view. The visitor, actor and spectator at the same time, is ‘forced’ to walk on a walkway that forms a sort of meander inside the room and to approach the back wall on which is wallpaper with an apparently decorative recurrent pattern.

The pattern consists of a neat, cold, digital geometry that reproduces in a visual loop a detail from Frank Hallam’s photograph En Masse, Sunners Seen from Pier 45 (1982). What the shot captures – and the visitor’s eye understands only when approaching it – is a scene that at first glance seems to refer to the ‘classic’ iconography of the bathers, but upon entering the installation it becomes clear that the chronological and geographical context is no longer mythological, but a real-life scene of the American queer community in the early 1980s.

One rediscovers the itch that the Salon’s academic jury must have had when it rejected Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe. Nevertheless, scenes of clasped male bodies have not been lacking in art, even going further back in time, but they have always had to find their legitimacy through mythological narration, such as Mantegna’s La zuffa degli dei marini [Battle of Sea Gods]. This slight sensation of epidermal discomfort, which is not so painful, does not really affect the normal course of the activities – of the overall enjoyment of the exhibition in which the installation is included – but is felt over time. In biology, stinging cells have small thorns that when touched release a substance that alerts the neuronal receptors; they are a defense organ that can inhibit predators from approaching the plant but also a treatment that has many benefits for the body. In the case of Pick Pocket Paradise, even a social one.

Arte e Critica, no. 97-98, Spring – Summer 2023, 24-30.

1. The work is part of the Flu水o project, curated by Davide Quadrio, from an idea by Luciana Galliano, under the artistic direction of Alessandro Sciarroni, which was presented at Pirelli HangarBicocca on 25 and 26 November 2021.

2. The fabrics are also a variation of Nam June Paik’s work, which in the historical version had adopted large papers.

3. As part of the exhibition Espressioni con frazioni, curated by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, Marcella Beccaria, Marianna Vecellio and Fabio Cafagna with curatorial coordination by Anna Musini, Castello di Rivoli, Turin, 24 April – 25 September 2022.