Una delle sintesi più fortunate e forse anche più utilizzate di Lévi-Strauss è quella relativa alla differenza tra bricoleur e ingegnere, laddove il primo crea utilizzando strumenti che non sono del mestiere mentre il secondo applica nel suo agire le leggi del progetto e della tecnica. Nel corso dei decenni, e con il variare del pensiero sui modi dell’arte e sullo statuto dell’artista, è stato inevitabile che la figura dell’artista venisse collocata ora più in sintonia con quella del progettista, ora più con quella del libero creatore, che lavora con ciò di cui dispone. Più spesso – e questo vale soprattutto per questi ultimi decenni, in cui si sono visti ripetutamente, e in un certo senso paradossalmente, convivere e intrecciarsi il dominio della tecnica e certe nostalgie preindustriali – l’artista lo ritroviamo volutamente ondivago tra i due poli, e questo sia che utilizzi gli strumenti propri del mestiere, della disciplina (l’ingegnere), sia che li inventi a partire da ciò che trova intorno a sé (il bricoleur).

Perché tornare a evocare il già così tanto citato Lévi-Strauss per ragionare sul lavoro di Campostabile? Perché uno degli aspetti meno evidenti ma più significativi del suo lavoro prende vita da un habitat quotidiano dove la tradizione di certi usi e di certi cibi occupa uno spazio considerevole. Cibi, oggetti, ma anche usi e rituali che si riferiscono a una civiltà contadina arcaica, e in quanto tale forse anche mitica (difficile non pensare al bricoleur costruttore di miti). Ma nel mondo di forme generato da Campostabile (Lorena Stabile, Alcamo 1989 e Mario Campo, Alcamo 1987), questi elementi non vengono riproposti in modo meccanico, e tanto meno analogico. Va fatto un passaggio, va innescata una trasformazione. E così la parola forma, che torna sovente nelle sue dichiarazioni, non possiamo che intenderla indissolubilmente legata alla processualità di cui risulta esito esplicito: meglio dunque parlare di «forma-processo».

A partire da quel paesaggio di riferimenti costituito dalla memoria dei sensi (in questo caso li metterei in quest’ordine: vista, tatto, gusto, olfatto, udito) e annettendo a quel paesaggio l’esperienza quotidiana e sconfinata del web, il duo dà vita a un ventaglio di procedure creative che lo porta a incarnare contemporaneamente le vesti del bricoleur e dell’ingegnere.

Faccio un esempio. C’è un lavoro che porta avanti da tempo e consiste nel produrre dei monocromi di piccolo formato che a uno sguardo distratto potrebbero far pensare a delle tecniche miste su carta leggera. Poi, indagando un po’, si scopre che sono il frutto di un processo chimico e concettuale estremamente più complesso. Partendo infatti dal desiderio di raccontare i colori nel modo più autentico, che sia rispettoso dell’origine naturale ma anche aderente ai rimandi mnestici personali, Campostabile realizza dei fogli colorati, monocromi e sottilissimi, a partire dagli ingredienti stessi della cucina, ossia impastando e cuocendo direttamente la materia edibile. Una materia che nella sua mente, nella sua esperienza e nella fisionomia colturale e culturale della sua terra rimanda esattamente al colore che ha in mente. Così ottiene dei fogli verdi di finocchietto, dei monocromi rossi fatti con il pomodoro, dei viola di cavolo rosso, dei gialli di zafferano, degli ocra/beige che derivano dai ceci, dei bianchi di mandorle.

In questo modo Campostabile estende l’idea di pittura – sulla quale si cementa il suo discorso poetico – fino ad annettere un territorio esperienziale che sintetizza elementi già di per sé densi di significato, ovvero: un materiale naturale/alimentare che ha un suo colore, un suo odore, un suo utilizzo tradizionale, una sua narrazione geografica, una sua storia culinaria; un procedimento antico quale la cottura del cibo (eccoci di nuovo con Lévi-Strauss e le implicazioni del cotto), con la messa a punto di una tecnica che attraverso la giusta consistenza, la giusta temperatura, il giusto tempo permette di arrivare alla produzione di un «foglio» e infine un costrutto formale come il monocromo che ha una sua lunga e specifica tradizione artistica ed estetica.

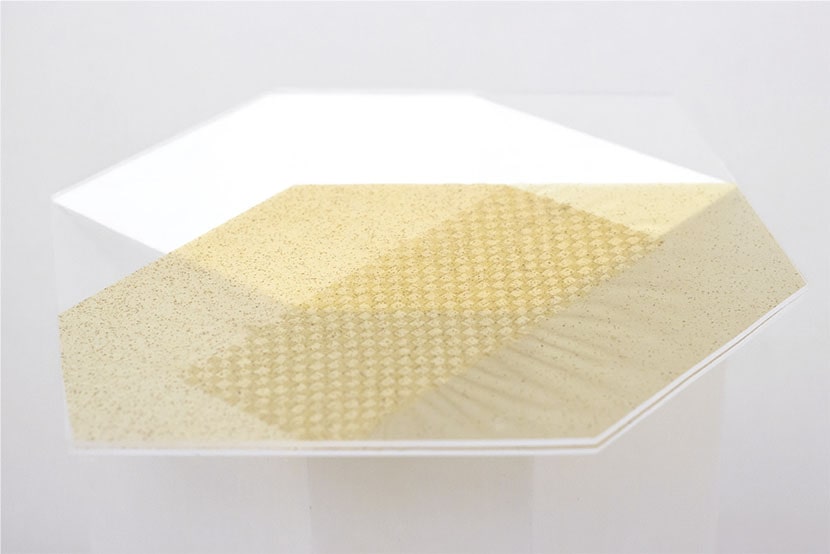

A questa sintesi, che esprime una visione del mondo già abbastanza circostanziata, e anche suggestiva, si aggiunge il fatto che quei fogli monocromi vengono spesso tagliati in una moltitudine di striscioline sottilissime che vengono poi intrecciate minuziosamente secondo schemi ortogonali (trama e ordito) a formare delle figure geometriche che poi si stagliano sulle campiture monocrome di partenza producendo complesse impaginazioni bidimensionali.

I temi messi in campo sono fin qui già parecchi, basterà soffermarsi su quello dell’intreccio, così presente nella letteratura post-coloniale e femminista, o su quello dell’artigianato contadino, così attuale nei termini della valorizzazione territoriale e della riconversione di specifiche aree geografiche, o su quello della pittura astratta e geometrica, così legata al pensiero tecnologico della modernità, per capire che l’equilibrio che il duo ricerca nella sua produzione, nel piccolissimo o nel grandissimo formato, è tutt’altro che casuale.

Si tratta di un ampliamento dell’armamentario disciplinare che diventa funzionale a introdurre nell’ambito semantico della pittura astratta una declinazione che, rovesciandone o comunque complicandone i presupposti modernisti, la pone di nuovo all’ordine del giorno.

Inserendo nel linguaggio della pittura geometrica la cultura e la ritualità del cibo, una significativa conoscenza delle piante, la sopravvivenza di una tecnica antica (l’intreccio delle ceste di vimini), la narrazione di un territorio mediante i suoi prodotti, quel linguaggio ne risulta vivificato e recupera pienamente la propria vocazione conoscitiva.

Percorsi nel tessuto. Dalla pittura al bivacco

Tra le diverse pratiche che Campostabile ha elaborato e sperimentato in questi anni, c’è un percorso originale nel territorio del tessuto condotto anch’esso all’insegna di un’idea di pittura. Una pittura che fa propri lo spazio e i volumi della scultura, le invenzioni della scenografia, i costrutti dell’architettura, e che contemporaneamente, come dicevo, ambisce a inseguire i colori delle piante e a comporsi della materia stessa dei cibi.

Campostabile legge tutto questo come un’articolazione dialogica di «zone di pittura», e dentro queste zone fa confluire il fulcro della propria ricerca.

Di progetto in progetto, le geometrie realizzate con i tessuti divengono via via più complesse. Partito da collage di abiti ritagliati dalle riviste patinate, e quindi da un lavoro di destrutturazione e di libera riconfigurazione dell’iconosfera quotidiana, il duo ha via via alleggerito il rimando esplicito alla moda, conservando soltanto la ricchezza cromatica e la verità tattile di un ampio campionario di produzione. E soprattutto ha conquistato la tridimensionalità, ha cominciato a elaborare strutture sempre più imponenti, architettoniche, morbidamente adagiate nei luoghi che le contenevano. Nessuna sopraffazione, nessuna trasformazione dello spazio dato, semmai una enigmatica coabitazione.

Non è questa l’occasione per esplorare il vasto bagaglio valoriale ed estetico che viene messo in campo dalla scelta del medium tessile, ma vale la pena farvi almeno riferimento al fine di inquadrare al meglio l’impostazione del loro procedere.

Potremmo dire che le composizioni di strutture e panneggi articolate nello spazio sono diventate dei paesaggi architettonici. Silenziosi, intrisi di umori e sospensioni novecenteschi ma in egual misura attori di spaesamenti tattili e visivi di ultima generazione.

Sono paesaggi abitabili con lo sguardo, ma che si sottraggono a una visione univoca, depistano il colpo d’occhio. Chiedono di essere percorsi, interrogati, prima di svelarsi.

Sono organismi leggeri, fragili, ma toccano registri alti.

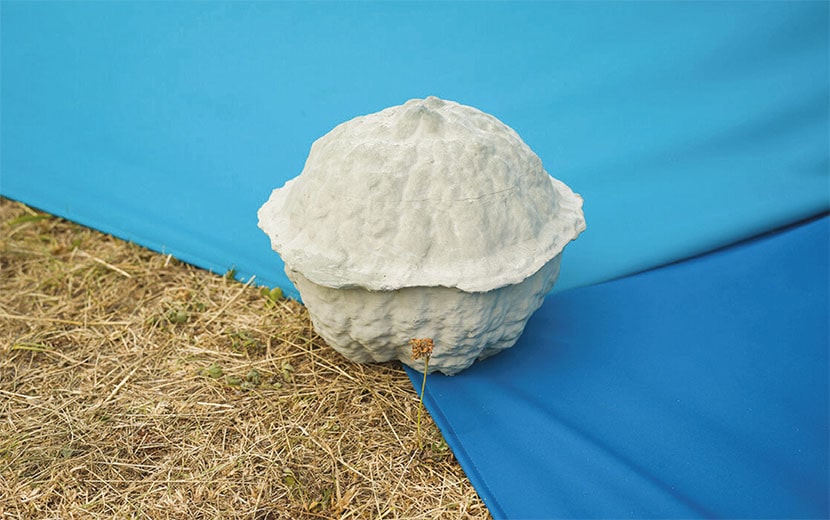

Invenzioni e atmosfere di un presente imprendibile si sovrappongono a segreti di un tempo antico. Piccoli oggetti, minuscole sculture ne occupano qualche altura nevralgica, o si nascondono dietro una piega. Talvolta derivano da stampe in 3D, altre volte sono fatti a mano, con l’argilla bianca. Possono essere dei calchi ma anche delle sculture modellate.

Nel paesaggio visionario e concreto di Campostabile stanno lì a richiamare dei brani di natura oppure custodiscono gli affioramenti dalla memoria.

Mettendo in fila alcune installazioni di questi ultimi anni (Palazzo Briuccia a Palermo/2018, Bagni Misteriosi a Milano/2019, Fondazione Zimei a Pescara/2020, Cornello dei Tasso per Una Boccata d’Arte/2021)1 si fa strada una visione abbastanza precisa che heideggerianamente ricorda come nel costruire ci sia l’urgenza dell’abitare: si costruisce perché si abita e non si abita perché c’è un costruito. Questi paesaggi architettonici definiti dalla composizione nello spazio di «zone di pittura» sono dunque dei luoghi da abitare, esistono perché c’è qualcuno che desidera risiedervi.

Di che abitazioni parliamo? Colorate, modificabili, precarie. Vi abita il pensiero di chi le ha progettate, vi abitano i piccoli oggetti/sculture, vi abita lo sguardo di chi, cinematicamente, le percorre con gli occhi (Allunga il passo è il titolo di uno di questi lavori recenti: un omaggio a un quadro omonimo di Gastone Novelli del 1967 che tra i vari intenti allude al viaggio visivo che va compiuto per raggiungere l’opera).

A Cornello, in Val Brembana, tra i ruderi della casa dei Tasso, ancorati al sedimento di natura che si è infiltrato tra ciò che resta di un antico mercatale, questo costruito abitabile per sguardo-mente-e-corpo ha assunto le connotazioni del «bivacco». Nelle intenzioni iniziali c’è la restituzione al luogo della sua fisionomia storica di punto nevralgico per il commercio, e quindi il tessuto scelto per l’opera è quello impermeabile e resistente utilizzato dai venditori ambulanti. È a loro che rimanda esplicitamente il senso primo del progetto, che punta a riportare alla memoria la Via Mercatorum, e quindi l’immagine dei grandi spostamenti del mondo medievale e rinascimentale, l’esperienza secolare e necessaria dell’incontro.

Ma parlando con Campostabile emerge anche, ad approfondire lo spessore del lavoro, il concetto del «bivacco». Questo termine è comparso spesso, di recente, negli incontri palermitani che fanno capo all’Osservatorio;2 esprime bene il modo individuale o collettivo con cui alcuni giovani sentono di rispondere alla condizione e alle questioni poste da questi tempi. Il bivacco, nell’accezione che viene fuori da questa piccola comunità, implica adattabilità, creatività, mobilità, contatto con la natura, informalità, condivisione, solidarietà. È un bivacco della mente, e con essa del corpo. È una risposta alle dicotomie di interno/esterno, privato/pubblico, permanente/impermanente in una società in cui la dimensione pervasiva della connettività virtuale rende difficile individuare lo statuto di realtà.

Pool, l’intervento ai Bagni Misteriosi, ragionava anch’esso in modo esplicito su una dimensione di coralità. Oltre che piscina, infatti, pool indica «un gruppo, un’entità collettiva, un organismo in condivisione»,3 scrive Campostabile. È un contenitore, come lo è in fondo anche una piscina. «In immersione, complice la materia che ci circonda, ci si ritrova tutti uniti dalla medesima condizione ma allo stesso tempo anche molto più concentrati su se stessi».4

Questi paesaggi/contenitore, compositi e impenetrabili, ci dicono molto, in realtà, su questa generazione.

Ambiguare

Si è detto che la dimensione dell’abitare gioca un ruolo centrale per Campostabile, il che spiegherebbe bene le ragioni per cui i suoi progetti partono sempre dal suo habitat, dal suo intorno; chiarirebbe il motivo per cui le sue forme intercettano spesso quelle del design e soprattutto rivelerebbe il senso della costante commistione di tecnologia e artigianato, calcolo progettuale, gesto arcaico e invenzione estemporanea.

Ma pur partendo dal quotidiano domestico – negli oggetti, nei gesti, in alcuni dei materiali – non si tratta di lavorare sul piano della referenzialità, non è quello l’orizzonte cui tende. Parte da ciò che è familiare per addentrarsi in ciò che non conosce. Cerca forme nuove che possano corrispondere alla sua visione, costruisce un universo differente, di libero equilibrio, di assoluta invenzione, carico di presente e di passato, qualche volta fors’anche post-apocalittico, comunque dotato di un tempo proprio.

Spesso il duo unisce elementi differenti per formare nuove unità. Un po’ come ha fatto nello scegliere di diventare un unico soggetto artistico. L’obiettivo non è mai la giustapposizione, o la somma, è la trasformazione: «il risultato ottenuto deve essere maggiore della somma degli elementi utilizzati».5 Quasi che l’invenzione possa ancora difenderci dall’entropia, e ancora di più possa farlo l’ambiguazione, allargando esponenzialmente le variabili dei significanti e dei significati.

Intanto, sul fondo, non smette di aleggiare quel respiro classico che li ha sempre condotti a pensare con la geometria. E quel respiro in questa fase assume la forma del bivacco.

Arte e Critica, n. 96, autunno – inverno 2021, pp. 31-37.

1. Le mostre alle quali faccio riferimento sono: Tutto Porto. Lo spazio cristallino del tungsteno, a cura di Daniela Bigi, Palazzo Briuccia, Palermo, 13 giugno – 31 luglio 2018; Immersione libera, un progetto di Marina Nissim a cura di Giovanni Paolin, in collaborazione con Galleria Continua, Palazzina dei Bagni Misteriosi, Milano, 2 aprile – 18 maggio 2019; Unfurniture, a cura di Massimiliano Scuderi, Fondazione Zimei, Montesilvano, Pescara, 26 settembre 2020 – 30 aprile 2021; Una Boccata d’Arte, un progetto di Fondazione Elpis e Galleria Continua, Cornello dei Tasso, Bergamo, 26 giugno – 26 settembre 2021.

2. L’Osservatorio Arti Visive è un organismo di ricerca fondato a Palermo nel 2008 da Daniela Bigi, Gianna Di Piazza e Toni Romanelli. Nato in seno all’Accademia di Belle Arti e dedicato alla scena artistica emergente, nel corso del tempo si è strutturato attraverso incontri periodici dedicati alle questioni, ai modi e agli obiettivi dell’arte contemporanea a partire dal ragionamento intorno all’opera. Partito come seminario, è via via cresciuto nella consistenza numerica e nel valore della comunità di intenti che lo anima, diventando un punto di riferimento cittadino e un luogo di incontro e confronto costantemente aperto anche ad artisti e curatori esterni all’Accademia.

3. Dallo statement di Campostabile che ha accompagnato l’opera Pool, pubblicato in Immersione libera. Una mostra d’arte contemporanea, catalogo della mostra (Milano, Palazzina dei Bagni Misteriosi, 2 aprile – 18 maggio 2019), Associazione Pier Lombardo, Milano 2019, p.59.

4. Ibidem.

5. Ivi, p.60.

One of Lévi-Strauss’ most fortunate and perhaps most used syntheses is the one concerning the difference between bricoleur and engineer, where the former creates using tools that are not of the trade whereas the latter applies the laws of the design and technique in his actions. Over the course of the decades, and with the variation of thought on the modes of art and on the status of the artist, it has been inevitable that the figure of the artist has been placed now more in tune with that of the designer, then more with that of the free creator, who works with what he has at his disposal. More often – and this is especially true in recent decades, in which the domination of technology and certain pre-industrial nostalgias have repeatedly, and in a certain sense paradoxically, coexisted and been intertwined – we find the artist deliberately wavering between the two poles, and this whether he uses the tools of his trade and discipline (the engineer) or invents them from what he finds around him (the bricoleur).

Why go back to evoking the already much cited Lévi-Strauss to reason about Campostabile’s work? Because one of the less obvious but more significant aspects of their work comes to life from an everyday habitat where the tradition of certain uses and certain foods occupies a considerable space. Foods, objects, but also customs and rituals that refer to an archaic agricultural society, and as such, perhaps even mythical (it is difficult not to think of the bricoleur as a builder of myths). But in the world of forms generated by Campostabile (Lorena Stabile, Alcamo 1989 and Mario Campo, Alcamo 1987), these elements are not re-proposed in a mechanical way, let alone an analogical one. A passage must be made, a transformation must be triggered. And so the word form, which often returns in their declarations, we cannot but understand as indissolubly linked to the processuality of which it is an explicit result: it is better to speak of «form-process».

Starting from that landscape of references made up of the memory of the senses (in this case I would put them in this order: sight, touch, taste, smell, hearing) and adding to that landscape the daily and boundless experience of the web, the duo gives life to a range of creative procedures that leads the duo to embody at the same time the roles of bricoleur and engineer.

I give an example. There is a work that they have been conducting for some time that consists in producing small-size monochromes that at a distracted glance might make one think of mixed media on light paper. Then, on investigating a little, one discovers that they are the result of an extremely more complex chemical and conceptual process. Starting in fact from the desire to tell colors in the most authentic way, which is respectful of the natural origin but also adherent to the personal mnestic references, Campostabile create colored, monochrome and very thin sheets, starting from the same cooking ingredients, that is directly mixing and cooking the edible material. A material that in their mind, in their experience and in the cultural and cultivation physiognomy of their land refers exactly to the color they have in mind. So they obtain green sheets of fennel, red monochromes made with tomatoes, purple ones of red cabbage, yellow ones of saffron, ochre/beige ones derived from chickpeas, white ones of almonds.

In this way, Campostabile extend the idea of painting – on which their poetic discourse is cemented – to the extent of adding an experiential territory that synthesizes elements already filled with meaning in themselves, namely: a natural/food material that has its own color, its own smell, its own traditional use, its own geographic narrative, its own culinary history; an ancient process such as cooking food (here we go again with Lévi-Strauss and the implications of cooked food), with the development of a technique that through the right compactness, the right temperature, the right time allows them to achieve the production of a «sheet» and finally a formal construct such as the monochrome that has its own long and specific artistic and aesthetic tradition.

To this synthesis, which expresses a vision of the world that is already quite detailed, and also suggestive, we can add the fact that those monochrome sheets are often cut into a multitude of very thin strips that are then meticulously interwoven according to orthogonal patterns (warp and weft) to form geometric figures that then stand out against the monochrome backgrounds of departure, producing complex two-dimensional layouts.

The themes put into play so far are already many; it is enough to dwell on the theme of weaving, so present in post-colonial and feminist literature, or on that of agricultural craftsmanship, so topical in terms of territorial valorization and the reconversion of specific geographical areas, or on that of abstract and geometric painting, so linked to the technological thought of modernity, to understand that the balance that the duo seeks in their production, in the very small or very large format, is anything but casual.

It is an extension of the disciplinary armamentarium that becomes functional to introduce into the semantic sphere of abstract painting a declination that, overturning or at least complicating its modernist assumptions, places it back on the agenda.

By inserting into the language of geometric painting the culture and rituals of food, a significant knowledge of plants, the survival of an ancient technique (the weaving of wicker baskets), the narration of a territory through its products, that language is enlivened and fully recovers its cognitive vocation.

Pathways in the fabric. From painting to bivouac

Among the various practices that Campostabile have elaborated and experimented with in recent years, there is an original itinerary in the territory of fabric, also conducted in the name of an idea of painting. A painting that embraces the space and the volumes of sculpture, the inventions of set design, the constructs of architecture, and that at the same time, as I said, aims at pursuing the colors of plants and at composing itself of the very matter of food.

Campostabile read all of this as a dialogical articulation of «painting areas», and allow within these areas that the crux of their research converge.

Project by project, the geometries created with fabrics become more and more complex. Starting from collages of clothes cut out of glossy magazines, and then from a work of deconstruction and free reconfiguration of the daily iconosphere, the duo have gradually lightened the explicit reference to fashion, retaining only the chromatic richness and tactile truth of a wide range of production. And above all, they have achieved three-dimensionality, have begun to elaborate increasingly imposing, architectural structures, softly placed in the places that contained them. No overwhelming, no transformation of the given space, if anything an enigmatic cohabitation.

This is not the occasion to explore the vast pool of knowledge of values and aesthetics that is brought into play by the choice of the textile medium, but it is worth at least referring to it in order to better frame the planning of their way of proceeding.

We could say that the compositions of structures and draperies articulated in space have become architectural landscapes. Silent, imbued with twentieth-century moods and suspensions, but in equal measure actors of tactile and visual bewilderments of the latest generation.

They are landscapes that can be inhabited with the gaze, but which elude a univocal vision, distracting the glance. They ask to be explored, questioned, before revealing themselves.

They are light, fragile organisms, but they touch high registers.

Inventions and atmospheres of an impregnable present overlap with secrets of an ancient time. Small objects, tiny sculptures occupy some crucial height, or hide behind a fold. Sometimes they derive from 3D prints, other times they are handmade from white clay. They can be casts but also molded sculptures.

In the visionary and concrete landscape of Campostabile they are there to recall pieces of nature or they guard the emergence from memory.

Putting together some of the installations of the last few years (Palazzo Briuccia in Palermo/2018, Bagni Misteriosi in Milan/2019, Fondazione Zimei in Pescara/2020, Cornello dei Tasso for Una Boccata d’Arte/2021)1, a fairly precise vision emerges that, in the way of Heidegger, recalls how in building there is the urgency of inhabiting: one builds because one inhabits and does not inhabit because there is a building. These architectural landscapes defined by the composition in space of «painting areas» are therefore places to inhabit, they exist because there is someone who wishes to dwell there.

What kind of dwellings are we talking about? Colorful, modifiable, precarious. The thoughts of those who have designed them live there, the small objects/sculptures live there, the gaze of those who, cinematically, walk through them with their eyes lives there (Allunga il passo [Lengthen your stride] is the title of one of these recent works: a tribute to a homonymous painting by Gastone Novelli from 1967 which, among other intentions, alludes to the visual journey that must be made to reach the work).

In Cornello, in Val Brembana, among the ruins of the Tasso family’s house, anchored to the sediment of nature that has infiltrated what remains of an ancient marketplace, this habitable building for the eye-mind-body has taken on the connotations of the «bivouac». In the initial intentions there is the restitution to the place of its historical physiognomy as a crucial point for trade, and therefore the fabric chosen for the work is the waterproof and resistant one used by travelling merchants. It is to them that the primary sense of the project explicitly refers, aiming to recall the Via Mercatorum, and therefore the image of the great movements of the medieval and renaissance world, the secular and necessary experience of meeting.

But speaking with Campostabile, the concept of the «bivouac» also emerges, deepening the importance of the work. This term has often appeared, recently, in the meetings in Palermo that are part of the Osservatorio;2 it expresses well the individual or collective way in which some young people feel they are responding to the condition and questions posed by these times. Bivouac, in the meaning that emerges from this small community, implies adaptability, creativity, mobility, contact with nature, informality, sharing, solidarity. It is a bivouac of the mind, and with it of the body. It is a response to the dichotomies of inside/outside, private/public, permanent/impermanent in a society where the pervasive dimension of virtual connectivity makes it difficult to identify the status of reality.

Pool, the intervention at the Bagni Misteriosi, also reasoned explicitly on a choral dimension. In addition to meaning swimming pool, in fact, pool indicates «a group, a collective entity, a shared organism»,3 write Campostabile. It is a container, just as a pool is, after all. «In immersion, with the aid of the matter that surrounds us, we all find ourselves united by the same condition but at the same time also much more focused on ourselves».4

These landscapes/containers, composite and impenetrable, actually tell us a lot about this generation.

Ambiguating

It has been said that the dimension of inhabiting plays a central role for Campostabile, which would well explain why their projects always start from their habitat, from their surrounding space; it would clarify why their forms often intercept those of design and, above all, it would reveal the sense of the constant mixture of technology and craftsmanship, design calculation, archaic gesture and extemporary invention.

But even though the duo start from everyday domestic life – in the objects, in the gestures, in some of the materials – it is not a question of working at a level of referentiality, that is not the horizon they aim at. They start from what is familiar to delve into what they do not know. They look for new forms that can correspond to their vision, they build a different universe, of free balance, of absolute invention, full of present and past, sometimes maybe even post-apocalyptic, however provided with its own time.

Often the duo combines different elements to form new units. A bit like they did in choosing to become a single artistic subject. The objective is never juxtaposition, or the sum, it is transformation: «the result obtained must be greater than the sum of the elements used».5 Almost as if invention can still defend us from entropy, and ambiguation can do so even more, exponentially widening the variables of meanings and signifiers.

In the meantime, in the background, that classical breath that has always led them to think with geometry does not stop hovering. And that breath in this phase takes on the form of the bivouac.

Arte e Critica, no. 96, autumn – winter 2021, pp. 31-37.

1. The exhibitions to which I refer are: Tutto Porto. Lo spazio cristallino del tungsteno, curated by Daniela Bigi, Palazzo Briuccia, Palermo, from June 13 to July 31 2018; Immersione libera, a project by Marina Nissim curated by Giovanni Paolin, in collaboration with Galleria Continua, Palazzina dei Bagni Misteriosi, Milan, from April 2 to May 18 2019; Unfurniture, curated by Massimiliano Scuderi, Fondazione Zimei, Montesilvano, Pescara, from September 26, 2020, to April 30 2021; Una Boccata d’Arte, a project by Fondazione Elpis and Galleria Continua, Cornello dei Tasso, Bergamo, from June 26 to September 26 2021.

2. The Osservatorio Arti Visive [Observatory on Visual Arts] is an organism for research and curatorial planning founded in Palermo in 2008 by Daniela Bigi, Gianna Di Piazza and Toni Romanelli. Born within the Academy of Fine Arts and dedicated to the emerging art scene, over time it has been structured through periodic meetings dedicated to issues, methods and objectives of contemporary art starting from the reasoning around the work. Started as a seminar, it has gradually grown in number and in the value of the community of purpose that animates it, becoming a reference point for young artists and a place for meeting and discussion constantly open to artists and curators outside the Academy.

3. From Campostabile’s statement that accompanied the work Pool, published in the catalog of the exhibition Immersione libera. Una mostra d’arte contemporanea (Milan, Palazzina dei Bagni Misteriosi, from April 2 to May 18 2019), Associazione Pier Lombardo, Milan 2019, p.59.

4. Ibidem.

5. Ivi, p.60.