In queste settimane ho riflettuto a lungo sul lavoro di Diego Perrone, ho percorso e ripercorso le traiettorie dense liberate, o imbrigliate, dalle sue forme, ho frugato tra le sue tante dichiarazioni, giocose, sorprendenti, puntuali proprio mentre paiono evasive. Ho letto e riletto i suoi titoli, piccole macchine verbali assemblate con un lirismo lucido, con un poetare chirurgico. La periferia va in battaglia, La terra piatta è una dimensione lirica del luogo come se regredire fosse inventare, Come suggestionati da quello che dietro di loro rimane fermo, Pendio piovoso frusta la lingua, Una mucca senza faccia rotola nel cuore.

Ho sempre seguito il suo lavoro, senza mai decidermi a scriverne. Perrone è uno di quei pochi artisti capaci di produrre malìa. Ma non lo trovi mai dove pensavi che fosse. E non è facile anticiparlo.

L’habitus ambiguo delle sue opere costringe ad avvicinarsi molto, richiede una consapevole scelta prossemica. Del corpo, dello sguardo. Talvolta, quando sei molto vicino, ti sembra di aver trovato una chiave per accedere al suo mondo; è lui in realtà che te ne ha suggerito il nascondiglio. Ma appena entrato, comprendi che lui è già altrove. Non ha lasciato biglietti. Solo dei micro indizi che gli sono sfuggiti nella fretta di afferrare un passaggio, o che ha lasciato di proposito per mimetizzare la scomparsa. Lo hai lasciato che scavava buchi nella terra e lo ritrovi che studia con accanimento la tecnica della fusione del bronzo; lo immaginavi impegnato a produrre animazioni digitali e lo scopri a scolpire il pvc; lo ricordavi intento a comprendere il funzionamento dell’orecchio e lo sorprendi a ricreare il rumore di una frana. Lo lasci con Boccioni e lo ritrovi con Wildt. Ti erano piaciute le lunghe piattaforme rosa, o nere, in salita, che delimitavano il suo altrove progettuale, e ti ritrovi a relazionarti con una sfilza di piedistalli bianchi. Al di qua e al di là dell’oceano.

Ti ricordavi, inoltre, di un suo autoritratto fotografico, un viso sorridente con una gallina sulla testa, ed eccoti piegato a guardare in controluce delle enormi teste di vetro, quasi un invaso per guizzanti carpe koi, oppure un campo in leggera altura da arare con un trattore. Sono suoi autoritratti.

Può anche succederti, camminando nel centro di Milano, di imbatterti in un grande orecchio in bronzo che funge da citofono. Pensi immediatamente a Perrone, ai tanti orecchi che hanno abitato, e ancora abitano, le sue sculture. E invece scopri che probabilmente era Perrone che pensava a Wildt e si innamorava della sua inventiva plastica, della sua seducente deriva visionaria. Invitato a una prova ancora oggi tra le più impegnative – sto pensando alla 55. Biennale di Venezia, del 2013 – è proprio a Wildt che sceglie di tributare un omaggio, riproducendone in due versioni nere la Vittoria del 1918-19, una testa marmorea inquietante e traslucida fissata nell’espressione di un urlo/sorriso, un pezzo in cui lo scultore milanese, nell’immediato dopoguerra, riuscì a restituire i sentimenti complessi e quasi profetici nei confronti di una vittoria che era costata troppo, sentimenti per i quali azzarda una forma celebrativa che si fa sintesi di eleganze liberty, di istanze astrattive, memorie arcaistiche, pathos espressionista.

Perrone concepisce in quell’occasione un progetto che arriva come una sterzata coraggiosa per i sempre più conformisti sguardi del mondo dell’arte. In una Biennale dedicata alle singolarità dei pensieri dell’arte, con forti sconfinamenti outsideristi e spiccata propensione verso saperi transdisciplinari, Diego si inserisce con una riflessione tutta interna all’arte, o meglio alla storia delle sue forme, che è inevitabilmente storia di un paese, delle sue visioni, dei suoi errori. Che l’artista lo ammetta o meno (e condivido la sua reticenza a svelare, la cura costante nel proteggere, quasi nascondere, le ragioni più profonde o meditate delle sue opere), l’urlo enigmatico di quella Vittoria, la posizione discussa di Wildt, l’invito implicito a riconfrontarsi con la tradizione italiana, e con la storia, inevitabilmente chiamata in causa, di un secolo di cui l’Italia è stata debole e ambigua coprotagonista, tutto questo non può non essere preso in considerazione di fronte a queste sue due sculture nere, belle e imprendibili. Diego, come sempre, gli ha saputo conferire una fertile leggerezza, ha piegato il discorso, che è di certo complesso e complessivo, sulla tecnica, sul formare, sul riprodurre, sul guardare…

Ed effettivamente, il pensiero intorno alla tecnica di esecuzione, sulla quale l’artista principalmente si sofferma, già di per sé, è vero, può essere letto come una sintesi asciutta ma esaustiva. Dentro il pensiero della tecnica, considerato dal versante dell’artista/artigiano e non da quello del calcolo quantitativo/razionale che ha dominato il XX secolo, è possibile riassumere, siglare in qualche modo, una visione del mondo. Nel corso dei decenni è stata una prospettiva cara al coté anarchico quella di difendere politicamente il fare artigianale, il mestiere, e oggi diventa uno scorcio prospettico interessante da cui guardare al presente per capire meglio come affrontare, come poter gestire creativamente un rapporto con il nostro passato.

Credo sia utile ricordare, inoltre, che presso lo studio di Wildt si sono formati Fontana e Melotti. Riferirsi al suo lavoro non può non richiamare, dunque, l’attenzione su un laboratorio, su un’attitudine alla sperimentazione di idee formali che avrà sviluppi della massima importanza nella scultura novecentesca. Non può non invitare a ripercorrere, e magari reimmaginare, le vicende delle forme, gli sguardi sulle forme, le prese di posizione assunte attraverso la scelta di certe forme. Il pensiero, i moventi, gli ideali o magari le inquietudini che le hanno generate.

Potrebbe essere anche interessante leggere quel lavoro di Perrone per la Biennale alla luce del dibattito che scaturì dalle posizioni sostenute da Harold Bloom nei primi anni settanta in merito all’angoscia dell’influenza,1 una questione che portava con sé, inequivocabilmente, quella del rapporto con la tradizione, oggi di nuovo attuale perché completamente da reinventare. Da I Pensatori di buchi a La fusione della campana a Vittoria (Adolfo Wildt), credo che Perrone non manchi mai di offrire, tra le tante suggestioni, quella di una familiarità, un’intimità con un’ampia e non necessariamente altisonante tradizione dell’arte occidentale, soprattutto italiana. Sembra piacergli curiosare dentro il proprio DNA di artista, pare raggomitolarsi tra le sue eliche e trovarvi conforto.

Quello che intriga è da una parte il suo rapporto con ciò che reinventa a partire dalla tradizione di cui fa spesso menzione, la vis demiurgica con la quale costruisce delle immagini a partire da un vasto mondo di riferimenti e di innamoramenti, dall’altra il tipo di vicinanza che crea tra chi guarda l’opera e l’ospite assente ma intrinsecamente evocato. Il suo è sempre un gioco tra presenza e assenza, tra detto, omesso e dissimulato.

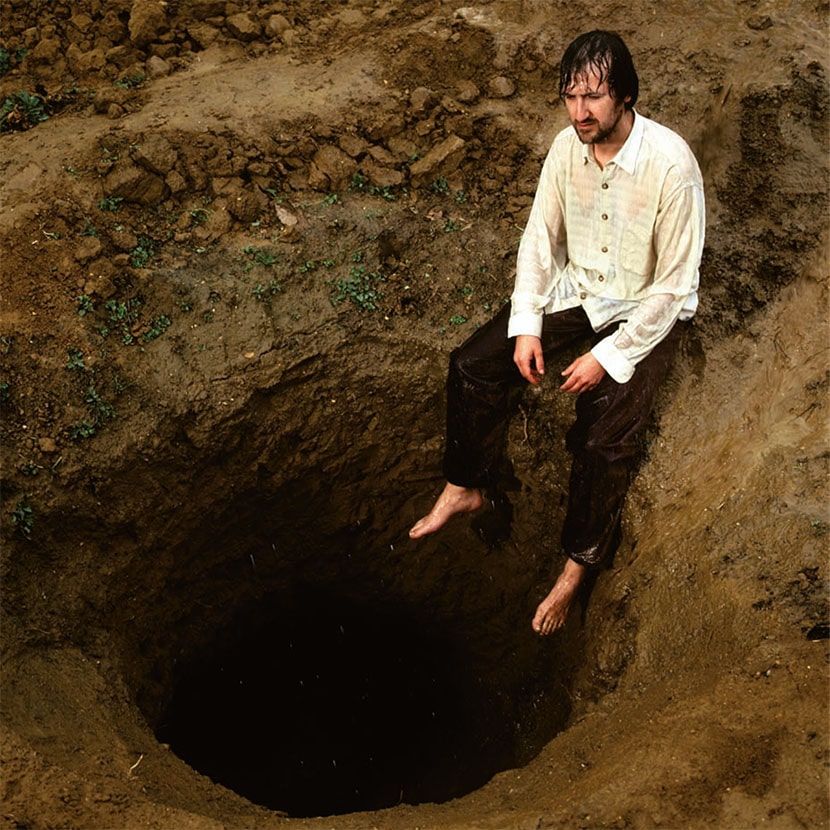

Quando parla di come ha realizzato I pensatori di buchi (2002), racconta che doveva preparare la sua prima personale a New York, da Casey Caplan, e preso dal panico, davanti al foglio bianco della mostra, ha cominciato a scavare. Magari dentro questa idea c’era qualche eco, anche distante, del rapporto tutto americano con la terra, i grandi spazi, le esperienze che sconfinano. Oppure invece ha cominciato a scavare per svuotarsi di tutti i segni che aveva dentro di sé, di tutti i segni che, come ci dicono appunto Bloom, ma anche Barthes, Deleuze, stanno lì prima che un artista, o un poeta, inizi a lavorare. Il foglio in realtà non è bianco, va svuotato per divenire bianco, così afferma chi ha cercato di studiare cosa avviene prima dell’atto poetico.

L’altra familiarità ricorrente nei lavori di Perrone è quella con alcuni oggetti (che potremmo estendere a degli animali, o a qualche dettaglio anatomico). Una familiarità che è sua, che gli appartiene, e una familiarità che ingenera in chi guarda. Quanto ci sono familiari, ormai, le enormi corna tenute tra le braccia come trofei da un manipolo di anziani effigiati nella posa dei guerrieri (o degli homines illustri, o forse ancora in quella dei papi, dei dogi, dei regnanti e delle loro spose); quanto ci appartengono le carpe che da alcuni anni ritroviamo serigrafate a pavimento o che guizzano nei suoi autoritratti a biro rossa o nelle trasparenti teste in vetro. Quanto ci siamo affezionati a quelle piccole o grandi orecchie disseminate nella sua produzione, con tanto di canale uditivo incorporato. C’è una pagina che Luciano Fabro dedica a questo tipo di sensibilità e una frase in particolare che la restituisce a tutto tondo: «il rapporto [con le cose, ndr.] non è un rapporto funzionale, ma è un rapporto di parentela […] Questa parentela è il risultato, la conseguenza di questa natura creata dall’artista».2 Poco prima aveva affermato che «l’opera d’arte è il modo umano di formulare la natura, a volte analogo ai modi vegetali, a volte analogo ai modi animali, o minerali o ad altri sistemi della natura».3 Si crea una “simpatia”, egli dice, tra l’artista e le cose, «che è anche indice di un rapporto innocente, archetipico, con la natura».

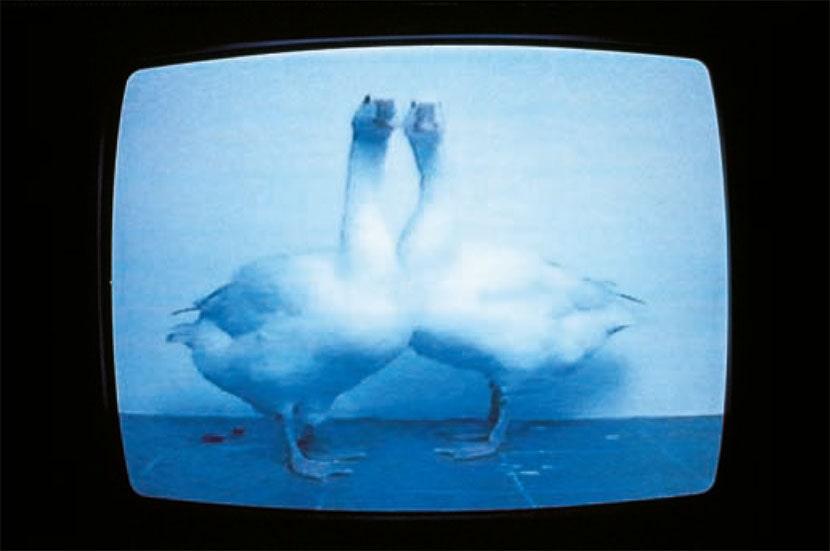

Bene, siamo arrivati a un’altra questione. La natura. Nello specifico il paesaggio naturale. Alcune delle opere più importanti di Perrone hanno a che fare con paesaggi o personaggi della natura (animali) e con elementi di un contesto agricolo. Lo si legge abitualmente in riferimento all’infanzia trascorsa in campagna, è l’artista stesso a dichiararlo. Dall’autoritratto con la gallina, alle tartarughe de La periferia va in battaglia (1998), alle oche del video Senza titolo (1995), ai paesaggi di Come suggestionati… (2001), al campo scavato dei Pensatori di buchi, alla radura in cui si spoglia Totò, ai trattori degli ultimi Selfportraits. Il rapporto diretto con la natura è quel tipo di componente autobiografica da cui potrebbe prendere vita un’intera poetica. Comincio a pensare che la campagna per Perrone sia un po’ come il mare per De Chirico, o per Marinetti. De Chirico pensa al mare di Volos, in Tessaglia, Marinetti al porto di Alessandria d’Egitto, che vedeva dalla sua casa natale, e quel mare diventa progressivamente una sorta di topos letterario, di luogo della mente, di sintesi figurale di una rete simbolica sempre più fitta. Non più singolare elemento di una narrazione autobiografica ma basamento e scheletro portante di un edificio simbolico che vuole rimanere segreto.

Chi cresce a contatto ravvicinato con la terra impara senza neppure accorgersene che tutto si trasforma costantemente, e questo ha un portato alternativamente rassicurante e sconfortante, in un groviglio di differenti scansioni temporali. Tempo e trasformazione sono due ambiti sia fisici che concettuali entro i quali è possibile incontrare l’infaticabile Perrone. E vi aggiungerei il territorio dello stupore. Il tempo può essere quello esteso che risale i millenni (pensiamo alle corna/reperto ostentate, o comunque orgogliosamente presentate dai guerrieri/anziani di Come suggestionati), o quello manipolabile con le tecnologie digitali (dalle sequenze in 3D del cane vecchio che muore a quelle dilatate dell’amante che taglia l’orecchio dell’amata, al primo piano lentissimo di Piedi realizzato per RAVE), o quello fisicamente esperito scavando profondi buchi nella terra, o ancora quello pregno di mistero e di attesa della cottura delle sculture di vetro. È il tempo che accompagna l’esistenza. È il tempo dentro il quale un corpo agisce e dentro il quale immagina. Tutto dipende, ogni volta, da quale angolazione lo si elegge a compagno di percorso: ora contemplandolo attraverso un attributo, ora sottoponendolo tecnologicamente a forzature, ora sentendoselo addosso nella cangianza stagionale mentre si è dentro la terra a scavare, ora implicandolo tra le linee di fuga di strutture plastiche astratte, ora osservandolo come co-agente di trasformazione durante la cottura di una massa vitrea plasmata e quindi scegliendolo come co-autore. Nulla potrebbe forse essere più congeniale al fare di Perrone del muoversi consapevolmente dentro il tempo e del giocare con la sua flessibilità, nulla potrebbe adattarsi con maggior generosità al suo sforzo di fissare l’impermanente, o per converso di muovere il permanente, magari anche soltanto attraverso il potenziale trasformativo del pensiero. Un pensiero mobile. Bello pensare di potergli dare una forma, poterlo solidificare in una forma…

I pensatori di buchi sono probabilmente proprio il tentativo di dare una forma non tanto al vuoto quanto al pensiero del vuoto, un tentativo di raffigurare una condizione imprendibile, passando prima attraverso una faticosa e lunga esperienza fisica e poi attraverso la sua sublimazione mediante la trasformazione in immagine. Così come il tema del video Vicino a Torino muore un cane vecchio (2005), come afferma l’artista stesso, non risiede nella morte del cane ma nel pensiero della morte del cane. Anche in questo caso, un’opera ottenuta attraverso una gestazione lenta del lavoro, con un programma rudimentale per l’animazione. Una gestazione lenta come quella di un quadro, con un lento lavoro di invenzione (non si tratta di documentare e montare pezzi di girato ma di inventare uno svolgimento, costruire una visione).

Si tratta dell’idea di una conoscenza ricercata attraverso l’immaginazione, che a sua volta si nutre di processi esperienziali. Spesso talmente esuberanti rispetto al soggetto dichiarato da avvolgerlo, comprimerlo, occultarlo quasi, e sostituirlo con il suo stesso intorno, fatto di processi, scarti, errori, fatica, trasformazioni. Viene da pensare a Bataille…

Nel caso delle varie edizioni della Fusione della campana tutto questo è evidente. La campana è là sul fondo, è una piattaforma evocativa, con la memoria acustica cui rimanda, con l’energia simbolica che emana, ma il cuore dell’opera, il primo piano, pulsa nell’immaginazione del processo di fusione, nel buco scavato nella terra, nel complesso dispositivo di strati che permette la definizione della forma, nell’immaginare la materia fluida che scende lungo i canali di scolo e poi si solidifica. L’opera sta nel pensare il processo che permette la creazione di una forma e nel dar forma a quel pensiero. Astraendo il processo stesso per poterlo sintetizzare ma al contempo conferendo all’opera finale la fragranza tattile e quasi uditiva del divenire una cosa.

Quando giovanissimo si autoritraeva con la gallina, era interessato a vedere con gli occhi di lei, cioè da una prospettiva sconosciuta. Così come quando cercava di immaginare cosa pensano le oche se lasciate da sole in una stanza si mettono davanti alla telecamera, si muovono simmetricamente per un certo tempo e poi si addormentano.

Si prova stupore. Quello stupore è conoscenza. Ma è anche momento di vibrazione, di aderenza con ciò che si guarda. Alterazione dei confini. Dimensione immersiva.

Davanti ai suoi soggetti enigmatici, o a certi elementi figurali utilizzati con pratiche stranianti, ho sempre pensato che sul fondo Perrone provasse una forte simpatia per Savinio, forse per De Chirico, e soprattutto per certi dispositivi formali surrealisti, svuotati quasi sicuramente delle suggestioni psicoanalitiche ma ancora carichi di quella possibilità di esprimere lo stupore, con tutta la carica dirompente che questo assume come risposta alla realtà (collettiva, individuale). Il sentimento che mi sembra più adatto per avvicinarsi alle sculture in vetro degli ultimi anni (presentate per la prima volta al Museion di Bolzano nel 2013, poi da Massimo De Carlo a Londra e nei mesi scorsi esposte da Casey Caplan a New York e Massimo De Carlo a Milano/Ventura) è proprio quello dello stupore. Guardare dentro una testa giungendo direttamente dall’orecchio, o dai capelli, a penetrare il suo interno liquido, trasparente, senza incontrare le ossa del cranio; trovarvi dentro una sorta di fondale marino o un campo da arare, desta meraviglia. Ma la meraviglia non si deve agli oggetti riconoscibili, non si applica al piano denotativo, referenziale. Si concentra sulla trasparenza, sul vuoto colorato che sta lì a connotare una testa che pensa e che si dà allo spettatore come autoritratto.

Queste mostre recenti sembrano giocate di nuovo intorno a un pensiero del vuoto, che è un luogo topico della scultura, ma sicuramente anche dell’immaginario di Diego. A fine anni novanta il vuoto lo si poteva trovare nella sua sospensione narrativa, nella dilatazione della visione, in una certa immobilità dei personaggi, e anche nelle piccole orecchie che disegnava o scolpiva; poi ha pervaso la crosta superficiale della terra, l’ha penetrata, vi si è andato a nascondere, in profondità. Successivamente ha preso la forma del suono, si è introdotto nell’orecchio, ha percorso i canali uditivi; si è creato nascondigli o alcove tra le curvature di bianche superfici serigrafate (l’interno dell’ambulanza con la mamma di Boccioni, le mucche al pascolo della Brodbeck), si è aggrappato a una moltitudine di piedistalli filiformi, quasi a voler alleggerire i pesi della materia. Oggi ha trovato una quiete temporanea nella scatola cranica, ne ha sconfitto le barriere ossee, è diventato chiaro e cangiante, si compiace della sontuosità delle sue trasparenze colorate, offre rifugio alle carpe aiutandole a schivare le esche e si estende come una sconfinata prateria per rumorosi trattori.

Quasi un percorso verso l’opus alchemico, o meglio, verso il pensiero dell’opus…

Nel corso del tempo, le tecniche di lavoro si sono avvicendate con irregolarità, gli strumenti del lavoro sono cambiati tante volte. In questo momento è la tecnica storica della fusione del vetro che lo ha affascinato, la possibilità di contemplare bidimensionalità e tridimensionalità in un solo pezzo, grazie allo studio minuzioso dei rapporti di peso e dei comportamenti dei minerali, degli ossidi, dei pigmenti. Un piccolo universo di relazioni, quasi una piccola cosmologia che nell’armonizzare i contrari, nel trovare il giusto posto agli elementi, produca stupore.

Questo lavoro è stato presentato la prima volta a Bolzano in una mostra intitolata Il Servo astuto. È divertente ricordare che una delle letture più interessanti dell’intera produzione di Plauto riconosce nel servus callidus il vero deus ex machina delle sue fabulae, la figura che con astuzie e inganni architetta le intere vicende, che ingegnosa, giocosa, ironica, anarchica dà il titolo alle commedie stesse, che creatrice di metafore e di allusioni diventa controfigura del poeta. Nel servo astuto, sempre a rischio delle catene ma orgoglioso acrobata dell’inventiva, Plauto finisce per incarnare se stesso, le astuzie e gli inganni si fanno metafora dell’atto creativo.

Siamo dunque dentro una complessa, giocosa, difficile metafora.

Arte e Critica, n. 88-89, primavera – estate 2017, pp. 78-86.

1. Harold Bloom, The Anxiety of Influence. A theory of Poetry, Oxford University Press, 1973, pubblicato in Italia nel 1983: Harold Bloom, L’angoscia dell’influenza. Una teoria della poesia, Feltrinelli, Milano 1983.

2. Luciano Fabro, Arte torna arte. Lezioni e conferenze 1981-1997, Einaudi, Torino 1999, p.141.

3. Ivi, p. 138

In recent weeks I have thought long and hard about the work of Diego Perrone. I retraced the dense trajectories freed, or harnessed, by his forms. I rummaged through his many playful, surprising and punctual declarations even when they seem evasive. I read and re-read his titles, small verbal machines assembled with a lucid lyricism, with a surgical poetry. The periphery goes into battle, The flat land is a lyrical dimension of the place as if regressing were inventing, like being impressed by what behind them remains stationary, A rainy slope whips the tongue, A faceless cow rolls in the heart.

I have always followed his work, without ever deciding to write about it. Perrone is one of those few artists capable charming. But you will never find him where you thought he was. And he is not easily predictable.

The ambiguous habitus of his works forces us to get very close and requires a conscious proxemic choice. Of the body, of the gaze. Sometimes, when you are very close, it seems as though you have found a key to access his world; in reality, he actually suggested the hiding place. But upon entering you realise that he is already somewhere else. He has left no notes. Only micro clues that he has left in hurry to escape, or has deliberately left to camouflage the disappearance. You left him digging holes in the ground and you find him carefully studying the technique of bronze casting; you were imagining him committed to producing digital animations and find him sculpting pvc; you were remembering him intent upon understanding the functioning of the ear and catch him recreating the sound of a landslide. You leave him with Boccioni and find him with Wildt. You liked the long red platforms, or black, upwards, that marked his projects elsewhere, and you find yourself relating with a slew of white pedestals. On this side or that side of the ocean.

You also remembered one of his photographic self-portraits, a smiling face with a chicken on its head, and there you are bending and looking against the light at the huge glass heads, almost a reservoir for darting koi carp, or a slightly hilly field to plow with a tractor. They are his self-portraits.

Walking in the centre of Milan, you may also come across a large bronze ear that serves as an intercom. You immediately think of Perrone, of the many ears that lived, and still live, his sculptures. But you discover that it was probably Perrone who thought of Wildt and fell in love with his plastic inventiveness, his seductive visionary. Invited to a test that is today still one of the most challenging – I am thinking of the 55. Venice Biennale, 2013 – it is precisely to Wildt that he chooses to pay tribute, reproducing in two black versions Victory of 1918-19, a haunting translucent marble head fixed with the expression of a scream/smile. It is a piece in which the Milanese sculptor, immediately after the war, was able to convey the complex and almost prophetic feelings towards a victory that had cost too much, feelings for which he gambles with a celebrative form that becomes a synthesis of art nouveau elegance, abstract instances, archaistic memories, expressionistic pathos.

For the occasion, Perrone conceived a project that comes as a courageous turn for the increasingly conformist eyes of the art world. In a biennial dedicated to the singularity of art thoughts, with strong outsider trespassings and a stand out propensity towards transdisciplinary knowledge, Diego arrives with a reflection entirely internal to art, or rather to the history of its forms, which is inevitably the history of a country, its visions, its errors. Whether the artist admits it or not (and I share his reticence to reveal the constant care to protect, almost hidden, the deeper thoughts or ideas behind his works), the enigmatic cry of Victory, the controversial position taken by Wildt, the implicit invitation to engage with Italian tradition and history, inevitably called into question, a century in which Italy was a weak and ambiguous co-protagonist, all this can not be taken into account before his two beautiful and elusive black sculptures. As always, Diego has been able to give a fertile lightness, he constructed the discourse, which is certainly complex and comprehensive, around technique, shaping, reproducing, looking…

And indeed, the thought around the execution technique, on which the artist primarily focuses, in itself can be read as a dry but exhaustive summary. Inside the thought about technique, considered from the point of view of the artist/craftsman and not from that of quantitative/rational calculation that dominated the twentieth century, it is possible to sum up, affirm in some way, a vision of the world. Over the decades a dear perspective of the anarchist coté has been to politically defend the artisanal, and the profession, and today it becomes an interesting position from which to view the present in order to better understand how to cope, how to creatively manage a relationship with our past.

I also think it is worth remembering that both Fontana and Melotti were formed in the studio of Wildt. Referring to his work cannot but recall, then, the focus of a workshop, an attitude of experimentation with formal ideas that see developments of the utmost importance in twentieth-century sculpture. It can not not invite one to retrace, and maybe reimagine, the sequences of the forms, the gaze at forms, the positions taken through the choice of certain forms. The thoughts, motives, ideals or even the concerns that generated them.

It might also be interesting to read Perrone’s work for the Biennale in light of the debate that arose from the positions taken by Harold Bloom in the early seventies on the anxiety of influence,1 an issue that unequivocally carried with it the relationship with tradition. Again, relevant today because it has to be completely reinvented. From I Pensatori di buchi to the La fusione della campana a Vittoria (Adolfo Wildt), I believe that Perrone never fails to deliver, amongst the many suggestions, that of a familiarity, an intimacy with a wide and not necessarily grandiose tradition of Western art, especially Italian. He seems to like exploring his own artist DNA. He seems to curl up in his propellers and find solace. What is intriguing on the one hand is his relationship with what he reinvents beginning from the tradition which he often mentions, the vis demiurgica with which he builds images from a vast world of references and passions, and on the other hand the type of closeness that he creates between the viewer and the work of the absent but intrinsically evoked host. His is always a game between presence and absence, between said, omitted and concealed.

When he speaks of how he realised I pensatori di buchi (2002), he recounts that he had to prepare for his first solo show in New York, at Casey Caplan, and panicking in front of the white sheet of the exhibition, he began to dig. Maybe in this idea there was some echo, even distant, of the all-American relationship with the earth, the great outdoors, the experiences that digress. Or instead he began to dig to empty himself of all the signs that he had inside himself, of all the signs that, as Bloom but also Barthes and Deleuze tell us, are there before an artist, or a poet, starts working. The sheet is not white, it should be emptied to become white, affirm those who have tried to study what happens before the poetic act…

The other recurring familiarity in the works of Perrone are some objects (which we could extend to the animals, or some anatomical details). A familiarity that is his, belongs to him, and a familiarity that breeds in the viewer. The huge antlers held in his arms like trophies of a handful of old people portrayed in the pose of warriors (or homines illustri, or perhaps even in that of the popes, doges, the rulers and their wives) are by now really familiar to us; the carp that we have for some years found silk-screened on the floor or that dart in his self-portraits in red pen or on transparent glass heads really belong to us. We have become so fond of those little or big ears scattered in his production, complete with built-in ear canals. There is a page that Luciano Fabro dedicated to this type of sensibility and a particular sentence that returns in the round, “the artist’s relationship (with things) is not a functional relationship, but a relationship of kinship […]. This relationship is the result, the consequence of the nature created by the artist”.2 Just a little earlier he had stated that “the work of art is the human way of formulating nature, sometimes similar to vegetable ways, sometimes similar to animals ways, or minerals or other natural systems”.3 A “sympathy”, he says, is created between the artist and things, “which is also a sign of an innocent archetypal relationship with nature”.

Well, we have arrived at another question. Nature. Specifically, the natural landscape. Some of the most important works of Perrone have to do with landscapes and characters from nature (animals) and with elements coming from an agricultural context. One reads it in reference to a childhood spent in the countryside, the artist himself declares. From the self-portrait with the hen, to the turtles from La periferia va in battaglia (1998), to the geese in the video Senza titolo (1995), to the landscapes of Come suggestionati… (2001), to the excavated field of Pensatori di Buchi, the clearing in which Totò undresses, to the tractors of the last Selfportraits. The direct relationship with nature is the kind of autobiographical component from which entire poetics could begin. I am beginning to think that the country for Perrone is a bit like the sea for De Chirico or Marinetti. De Chirico thinks of the sea of Volos, at Tessaglia, while Marinetti thinks of the harbour of Alexandria in Egypt that he saw from the house in which he was born, and that sea gradually becomes a sort of literary topos, the place of the mind, figural synthesis of a symbolic increasingly dense network. No longer singular element of an autobiographical narration, but base and supporting skeleton of a symbolic building that wants to remain a secret.

Those who grew up in close contact with the land learn without even realising that everything changes constantly, and this can be alternately reassuring and disheartening, in a tangle of different time frames. Time and transformation are two areas – physical and conceptual – within which it is possible to meet the tireless Perrone. And I would add the territory of wonder. Time can be that which is extended and dates back thousands of years (think of the horns/ostentatious find, or at least proudly presented by the warriors/the elderly by Come suggestionati), or that which can be manipulated with digital technologies (from sequences in 3D of the dying cane vecchio [old dog] to the dilated sequences of the lover who cuts the ear off his beloved, on the slow close-up of Piedi realised for RAVE), or that physically experienced by digging deep holes in the ground, or even that imbued with mystery and hope of firing the glass sculptures. It is the time that accompanies existence. It is the time in which a body acts and imagines. It all depends, each time, upon the angle for which you choose it as a travel companion: now contemplating it through an attribute, subjecting it to technological forcing, hear it in an iridescent season while digging inside the earth, now implicating it between the lines that drain abstract plastic structures now observed as co-agent of transformation during the firing of a vitreous mass molded and then choosing him as co-author. Nothing could possibly be more congenial to Perrone than consciously moving in time and playing with its flexibility, nothing could adapt with greater generosity to his effort to secure the impermanent, or conversely to move the permanent, maybe only through the transformative potential of thought. A mobile thought. It is wonderful that you can give him a form, solidify him in a form…

I pensatori di buchi are probably an attempt to give form not so much to emptiness but to the idea of emptiness, an attempt to portray an elusive condition, passing first through a long and tiring physical experience and then through its sublimation through the transformation into image. This is also the case with Vicino a Torino muore un cane vecchio (2005), where the theme, as the artist himself affirms, is not the death of the dog but the idea of the death of the dog. Even in this case, the work is arrived at through a slow development of the work, with a rudimentary program for the animation. A slow development like that of a painting, with a slow labour invention (this is not to document and assemble pieces of a shot but to invent a development, build a vision, charging it to the maximum). It is about the idea of a sophisticated form of knowledge searched for in the imagination, which in turn feeds on experiential processes. These processes are often so exuberant with respect to the declared subject that they envelop, contain, and almost absorb it, and replace it with his own surroundings, made of processes, waste, errors, fatigue, transformations.

This is evident in the various editions of the Fusione della campana. The bell is there at the bottom; it is an evocative platform; which refers to an acoustic memory and the symbolic energy that it emanates from; but the heart of the work, that is, the foreground, pulsates in the imagination of the melting process; in the hole dug in the earth; in the complex layering system that allows the definition of the form; imagining the fluid matter which descends along the gutters and then solidifies. The work lies in thinking the process that allows for the creation of a form and giving form to that thought. It abstracts the process itself in order to be able to synthesise it and at the same time gives the final work the tactile and almost auditive fragrance of becoming a thing.

When he was really young he made self-portraits with a hen, he was interested in seeing with her eyes, that is, from an unknown perspective. Just as when he tried to imagine what geese think when left alone in a room they put themselves in front of the camera, move symmetrically for a while and then fall asleep.

One is astonished. This astonishment is knowledge. But it is also a moment of vibration, of adherence to what we are looking at. Alteration of boundaries. Immersive dimension.

Before his enigmatic subjects, or certain figurative elements implemented through alienating practices, I have always thought that Perrone had a sympathy for Savinio, perhaps for De Chirico, and especially for certain formalist surrealist devices. Although emptied of psychoanalytic suggestions, his works are still able to express astonishment, and indeed, all of its explosive power in response to reality (collective, individual). The feeling that seems most appropriate when approaching the glass sculptures of recent years (presented for the first time at the Museion in Bolzano in 2013, then at Massimo De Carlo in London and in recent months exposed at Casey Caplan in New York and Massimo De Carlo in Milan/Ventura) is precisely that astonishment. Looking inside a head coming directly from the ear, or from the hair, to penetrate its interior liquid, transparent, without encountering the bones of the skull; finding yourself in a kind of seabed, or a tithe, little wonder. But the wonder is not due to recognizable objects, it does not apply to the denotative, referential sphere. It focuses on transparency, on the coloured void that is there to connote a head that thinks and that thinks and presents itself to the viewer as a self-portrait.

These recent exhibitions seem to revolve around an idea of the void – a topical site of sculpture, but certainly also in the imaginary of Diego. In the late nineties the void could be found in its narrative suspension; in the expansion of vision; in the certain immobility of the characters; and even in the small ears that he drew or sculpted; then it permeated the surface crust of the earth, penetrated it, and hid in its depths. The void then took the form of sound, it entered the ear and travelled through its canals; caches or alcoves between the curvatures of white screen-printed surfaces (the interior of the ambulance with Boccioni’s mother, grazing cows) were created; it clung to a multitude of filiform pedestals; almost with the intention of lightening the weight of matter. Today it has found a temporary haven in the cranium; it has defeated its bony barriers; it has become clear and iridescent; it welcomes the sumptuousness of its coloured transparencies; it provides shelter for the carp helping them to avoid the esche and it expands like a wide field for noisy tractors.

Almost a path to the alchemical opus, or rather, towards the idea of the opus…

Over time, working techniques have alternated with irregularities, and the tools have changed many times. At the moment the historical technique of the fusion of glass fascinates him, as well as the possibility of incorporating two-dimensionality and three-dimensionality in one piece, thanks to the detailed study of the weight ratios and of the reactions of the minerals, oxides and pigments. A small universe of relationships, almost a small cosmology that, harmonising contraries and finding the right place for elements, produces astonishment.

This work was presented for the first time in Bolzano in an exhibition entitled Il Servo astuto. It’s worth remembering that one of the most interesting readings of the entire production of Plautus in servus callidus recognises the true deus ex machina of fabulae Plautus, the figure who in a cunning and deceitful way orchestrates the whole scenario. That ingenious, playful, ironic, anarchist gives the title to such comedies; that creator of metaphors and allusions become stunt poet. In the servo astuto, always at risk of chains but a proud acrobat of inventiveness, Plautus ends up incarnating himself, cunningness and deceit become metaphors for the creative act.

We are therefore in a complex, playful, difficult metaphor.

(Translation by Vashti Ali)

Arte e Critica, no. 88-89, spring – summer 2017, pp. 78-86.

1. Harold Bloom, The Anxiety of Influence. A theory of Poetry, Oxford University Press, 1973, published in Italy in 1983: Harold Bloom, L’angoscia dell’influenza. Una teoria della poesia, Feltrinelli, Milan 1983.

2. Luciano Fabro, Arte torna arte. Lezioni e conferenze 1981-1997, Einaudi, Turin 1999, p.141.

3. Ivi, p.138.