A PARTIRE DA UN RAGIONAMENTO INTORNO ALLE OPERE DI JASON DODGE E GIOVANNI TERMINI, ESPOSTE DI RECENTE NELLA MOSTRA L’UMANITÀ DEGLI OGGETTI, NEGLI SPAZI DI KAPPA NÖUN A SAN LAZZARO DI SAVENA (BO), SIMONE CIGLIA, CURATORE DEL PROGETTO, APPROFONDISCE QUELLA CHE È STATA DEFINITA COME TEORIA DELLE COSE.

The eagerness of objects to

be what we are afraid to do

cannot help but move us.*

(Frank O’Hara)

«Cominciamo a confrontarci con la coseità (thingness) degli oggetti quando smettono di lavorare per noi: quando il trapano si rompe, quando l’auto si ferma, quando la finestra si sporca, quando il loro flusso all’interno dei circuiti di produzione e distribuzione, consumo ed esposizione, è stato arrestato, per quanto momentaneamente. La storia degli oggetti che si affermano come cose, quindi, è la storia di un mutato rapporto con il soggetto umano e così la storia di come la cosa in realtà nomina, più che un oggetto, una particolare relazione soggetto-oggetto. Mentre circolano nelle nostre vite, guardiamo attraverso gli oggetti (per vedere cosa rivelano sulla storia, la società, la natura o la cultura – soprattutto, cosa rivelano su di noi), ma intravediamo soltanto le cose».1 Delineando quella che è stata codificata come Thing Theory (Teoria delle cose) al principio degli anni 2000, Bill Brown prendeva le mosse dalla distinzione heideggeriana fra oggetto e cosa: se il primo è legato al dominio della funzionalità, la seconda si genera dalla trasformazione dell’oggetto quando cessa la sua funzione. Brown era stato abile nell’applicare la sua teoria al campo letterario, investigando la relazione fra umani e oggetti nell’ambito della produzione americana a cavallo fra Otto e Novecento. Con l’evidenza ancora maggiore data dall’incombenza fisica, è tuttavia nell’arte visiva che vediamo dispiegarsi il regno degli oggetti. La loro proliferazione, soprattutto a partire dal secondo dopoguerra, è riassunta nello spostamento d’asse rilevato da Baudrillard: se la modernità ha costituito lo sfondo storico per l’emergenza del soggetto, il dominio dell’oggetto è invece il marchio della postmodernità.

Un gufo tassidermizzato.

Una serie di ostacoli di materiali e forme diverse.

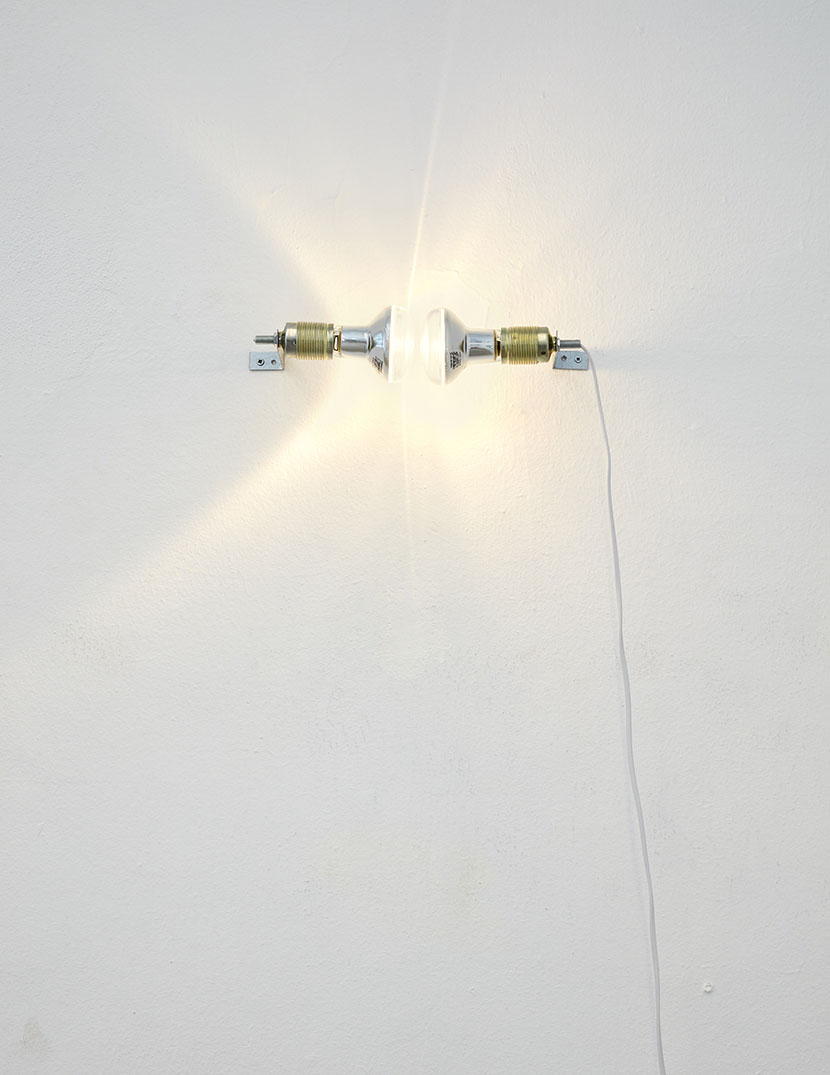

Una coppia di lampadine appese alla parete, affrontate.

Due coperte ripiegate e poggiate a terra.

Un fascio di nove travetti di legno legati insieme.

Questi gli oggetti – o forse le cose, direbbe Heidegger – radunati per questa mostra. Sono stati prodotti – o, meglio, pensati e assemblati – da due artisti: Jason Dodge e Giovanni Termini. Pochi anni ne separano le date di nascita – 1969 il primo, 1972 il secondo – più ampia è invece la distanza geografica – Stati Uniti e Italia – ma un’attitudine condivisa giustifica l’appaiamento in questa occasione. Un’attitudine che trova appunto nella dimensione oggettuale il nucleo generativo, fino all’ipotesi di una thing practice (pratica delle cose).

«Non sappiamo cosa siano la maggior parte delle cose, o dove siano state, o cosa ci sia dentro».2 (Jason Dodge)

In un’intervista, Dodge descrive la propria pratica come fondata sull’uso di oggetti quotidiani: la loro presentazione all’interno degli spazi espositivi convenzionalmente associati all’arte, consente secondo l’artista uno sguardo più profondo sul mondo e la possibilità di svelare l’«umanità degli oggetti che usiamo».3 Attraverso un processo di trasmutazione di natura poetica – non è incidentale l’interesse dell’artista per la poesia e la sua attività in campo editoriale – Dodge svela il potenziale narrativo insito nell’oggettualità, anche quella più feriale. Tramite semplici gesti di marca concettuale (come prelievi, accostamenti, assemblaggi), questa dimensione mondana viene riscattata in una apertamente umanistica: «In generale, sono le persone, i soggetti che mancano in quello che faccio – spiega l’artista – Ti sto parlando di loro, ma essi non ci sono. È come se stessi usando la sensazione di perdita come materiale».4 L’esempio più illuminante è fornito dalla coppia di lampade affrontate in Untitled (2021): l’una, collegata alla presa elettrica, è accesa; l’altra, priva di alimentazione, s’illumina grazie al riflesso della compagna. Pur partendo da una condizione asimmetrica, addirittura opposta, una comunione è raggiunta attraverso la metafora del bacio luminoso.

La coseità – apparentemente ottusa – sembra dominare le due coperte, diverse per dimensioni e fattura ma simili nel colore, piegate e poggiate a terra. Questo carattere, che le renderebbe indistinguibili da normali oggetti di uso quotidiano, è tuttavia smentito dal titolo. Nel primo caso, esso informa che Ad Alvorada, in Brasile, Vera Junqueira ha tessuto filati di lana del colore della notte e della stessa lunghezza della distanza dalla terra a sopra il tempo meteorologico. Nel secondo, invece, che A Torino, Cristina Donato ha tessuto un filato di lana merino che è del colore della notte e di una lunghezza pari alla distanza dalla terra a sopra il tempo meteorologico. Parte di una serie, le coperte sono accomunate dal medesimo processo di tessitura, che prevede l’utilizzo di diverse tipologie di filato la cui lunghezza è pari alla distanza fra la terra e la troposfera, lo spazio oltre il quale il tempo meteorologico (invocato nel titolo) non esiste. Attraverso questo dispositivo testuale, caratteristico del paradigma concettuale, lo spettatore ha accesso mentalmente a uno spazio altrimenti esperibile solo nell’esperienza di volo aereo, uno strato di significato che proietta il manufatto oltre la sua materialità. Un ulteriore aspetto ordito in questa serie ha a che fare con l’agenzia umana. Replicando un altro topos concettuale, la realizzazione del lavoro è delegata a una tessitrice. «Le cose non esistono senza essere piene di persone»,5 ricorda Bruno Latour: qui l’oggetto svela la sua umanità dichiarando il proprio processo esecutivo, a opera di una persona identificata da nome e cognome.

La chiave interpretativa contenuta nel titolo si fa più enigmatica nel caso del gufo. Il titolo asserisce che all’interno dell’animale imbalsamato è nascosto un diamante: questo, tuttavia, è invisibile allo spettatore, come pure il contenuto della scatola di cartone su cui l’uccello è adagiato (è privilegio del collezionista poterla aprire e scoprire il lenzuolo e il cuscino che l’autore ha apparecchiato all’interno). Qui è il processo di tassidermia a ridurre un essere vivente allo stato di cosa. La morte, riflette Michael Taussig a proposito delle poesie di Sylvia Plath, sembra possedere la capacità di trasformare in oggetti le persone e allo stesso tempo riportare in vita oggetti inanimati.6 In questa duplice trasmutazione sembra rimasto appollaiato anche il rapace: esso custodisce inoltre al suo interno qualcosa di prezioso ma inaccessibile, se non attraverso il pensiero: «La scultura è uno dei pochi luoghi al mondo in cui puoi descrivere cose a cui non puoi accedere nel modo consueto»,7 dice Dodge.

Lo stesso vitalismo materialistico abita la scultura di Giovanni Termini. Fermamente situato in uno spazio che si proietta nella dimensione temporale, aperto al processo che ne detta i materiali, il lavoro di Termini si nutre – come dichiara l’autore – «proprio dei conflitti che cerca, inutilmente, di sedare. Non vedo altri stimoli alla ricerca»,8 conclude.

Questa tensione agonistica è esplicitata fin dal titolo di un’opera che afferma la nozione di arte come inciampo, impedimento, intralcio (Ostacoli, 2019). L’installazione allinea appunto una serie di ostacoli: un dissuasore cordonato, un dosso stradale, un’asta sorretta da una coppia di treppiedi, una struttura di tubi innocenti, una putrella, una transenna; la sequela è unificata da un’uniforme verniciatura celeste. Nata dall’incontro con un dispositivo museale, l’opera allunga lo spunto iniziale di critica istituzionale a una più ampia considerazione del rapporto fra opera e spettatore, questione cruciale nella contemporaneità. Fin dall’emblematico readymade duchampiano – un attaccapanni fissato a pavimento che si trasforma in inciampo per l’artista e quindi per lo spettatore (Trébuchet, 1917) – l’opera contemporanea sembra descrivere una vera e propria genealogia della caduta.9 Erede di questa tradizione (apparentemente) rovinosa, Termini la eleva al parossismo attraverso la moltiplicazione e variazione del fattore di ostruzione. Il percorso atletico, tuttavia, straniato cromaticamente, è ingaggiato come produttivo: l’ostacolo è ridefinizione di una traiettoria, scoperta di una possibilità imprevista, atto generativo.

Ostacoli ribadisce la qualità oggettuale che caratterizza il lavoro dello scultore dagli esordi, come puntualizza Marco Bazzini: «Nelle sue opere Termini non introduce oggetti da lui realizzati manualmente o in altra maniera artigianale. Nessun corpo, quindi, appare estraneo o incongruo rispetto ai caratteri dei materiali reperibili sul mercato che danno origine alle sue conformazioni. Nelle sue sculture la qualità degli oggetti mantiene un criterio oggettivo (nel senso proprio di una identità dell’oggetto)».10 Questa postura oggettiva è però contraddetta da un’antropomorfizzazione a volte trasparente nei titoli delle opere, che tradiscono un investimento emotivo: la scultura di Termini è In attesa, Necessariamente tesa, Momentaneamente aperta, Disarmata da se stessa, Stretta all’angolo, Pregressa, Delimitata, Riversa. Così, anche la seconda opera in esposizione è Inclinata (2009). Qui nove morali – travetti di legno impiegati in edilizia nell’orditura delle coperture lignee – sono uniti in file di tre e tenuti insieme da un nastro adesivo americano di colore rosso. Sulla sommità di otto elementi è alloggiato un cubo in marmo di Carrara; il nono è invece semplicemente verniciato di bianco (la differenza è tradita dalla mancanza di ortogonalità). L’insieme è poggiato, inclinato, sulla parete. Questo stato di transitorietà suggerisce un senso di temporaneo abbandono, organizzato tuttavia per una possibile rimessa in funzione. Un momento di equilibrio che, nella molteplicità di elementi fra loro coesi, potrebbe aprirsi a metafora sociale.

Seguendo in parallelo la doppia traiettoria degli artisti, la Thing Theory entra all’inizio degli anni ’10 in una seconda fase, affollata di voci dalle molteplici intonazioni: il decentramento del soggetto, l’ontologia orientata all’oggetto, l’ecocritica, il postumano. Fra queste, l’«ecologia politica delle cose» tracciata dalla teorica politica Jane Bennett postula l’esistenza di una «materialità vitale» («vital materiality») che abita tanto i corpi animati quanto quelli inanimati.11 Se il suo invito è rivolto a riconoscere le forze non-umane come agenti attivi nella storia, l’arte da tempo esibisce la vitalità della materia, e il lavoro di Dodge e Termini ne è una testimonianza. Gli artisti sembrano rivendicare quel «destino degli oggetti» che Baudrillard lamentava negletto, ridotto a povertà a scapito dello «splendore del soggetto».12

«Ed ecco le cose più solide sfuggire alla prigionia del proprio volume, quelle più comuni smettere i panni ormai logori del familiare. Improvvisamente nude, le cose scoprono se stesse. Le cose più minuscole divengono i germi di mondi interi. Un oggetto può così essere il polo d’una meditazione sull’universo. Come dicono i filosofi, ciascun oggetto può diventare una “apertura sul mondo”».13 (Gaston Bachelard)

Settembre 2022

* L’entusiasmo degli oggetti di / essere ciò che abbiamo paura di fare / non può fare a meno di commuoverci.

1. B. Brown, Thing Theory, in «Critical Inquiry», vol. 28, n. 1, Things, Autumn 2001, p. 4.

2. J. Dodge, dichiarazione dell’artista, in https://caseykaplangallery.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/JDPress-Kit.e.pdf.

3. Collezione Maramotti – Jason Dodge, A permanently open window, in https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1i5UtYZJ39o.

4. J. Dodge, dichiarazione dell’artista, in https://caseykaplangallery.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/JDPress-Kit.e.pdf.

5. B. Latour, “The Berlin Key or How to Do Words with Things”, trad. di Lydia Davis, in Matter, Materiality, and Modern Culture, ed. P. M. Graves-Brown, Routledge, Londra – New York 2000, pp. 10, 20.

6. Michael Taussig, Dying Is an Art, Like Everything Else, in «Critical Inquiry», vol. 28, n. 1, Things, Autumn 2001, pp. 305-316.

7. Collezione Maramotti – Jason Dodge, cit.

8. Giovanni Termini, statement inedito.

9. Questo aspetto è ben ricostruito da Alberto Zanchetta in G. Termini, A. Zanchetta, Quella cosa su cui inciampi, la c., 2020.

10. M. Bazzini, “Quando il cantiere diventa forma”, in Giovanni Termini, Gli Ori, Prato 2021, p. 140.

11. J. Bennett, Vibrant Matter. A political ecology of things, Duke University Press, Durham 2010.

12. J. Baudrillard, Fatal strategies, trad. di P.Beitchman e W.G.J. Niesluchoski, ed. Jim Fleming, New York, 1990, p. 111.

13. G. Bachelard, Il diritto di sognare, trad. di M.Bianchi, Edizioni Dedalo, Bari 1975, p. 155.

THE HUMANNESS OF OBJECTS. JASON DODGE – GIOVANNI TERMINI

The eagerness of objects to

be what we are afraid to do

cannot help but move us

(Frank O’Hara)

“We begin to confront the thingness of objects when they stop working for us: when the drill breaks, when the car stalls, when the window gets filthy, when their flow within the circuits of production and distribution, consumption and exhibition, has been arrested, however momentarily. The story of objects asserting themselves as things, then, is the story of a changed relationship to the human subject and thus the story of how the thing really names less an object than a particular subject-object relation. As they circulate through our lives, we look through objects (to see what they disclose about history, society, nature, or culture – above all, what they disclose about us), but we only catch a glimpse of things.”1 Outlining what was codified as Thing Theory at the beginning of the 2000s, the literary theorist Bill Brown started from the Heideggerian difference between object and thing: if the former is linked to the domain of functionality, the latter is generated by the transformation of the object when its function ceases. Brown was keen to apply his theory to the literary field, investigating the relationship between humans and objects in American literature at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. However, it is in the art world that we see the realm of objects unfolding with the greater weight of their physicality. The proliferation of objects, especially after World War II, is summed up in the shifting of the subject-object axis noted by Baudrillard: if modernity constituted the historical background for the emergence of the subject, the dominion of the object is instead the hallmark of postmodernity.

A taxidermized owl.

A series of obstacles of different materials and shapes.

A pair of light bulbs hanging on the wall, facing each other.

Two blankets folded and placed on the ground.

A bundle of nine wooden joists tied together.

These are the objects – or perhaps the things, Heidegger would say – gathered for this exhibition. They were made – or, better, designed and assembled – by two artists: Jason Dodge and Giovanni Termini. Only a few years separate the dates of their birth – the former born in 1969, the latter in 1972, but a wider geographical distance divide their countries of origin – United States and Italy. Yet a shared attitude motivates their pairing on this occasion, an attitude that finds its generative nucleus in the objectual dimension, leading up to the hypothesis of a thing practice.

“You don’t generally know what things are by looking at them. Nor do you know what they were, what they have inside of them or what they’ve touched.”2 (Jason Dodge)

In an interview, Dodge describes his practice as founded on the use of everyday objects: their presentation within exhibition spaces conventionally associated with art, allows a deeper look at the world and the possibility of unveiling the “humanness of the objects we use.”3 Through a process of transmutation in a poetic register – the artist’s interest in poetry and his activity in the publishing field is not incidental – Dodge reveals the narrative potential inherent in objectivity, even of the most quotidian variety. Through simple conceptual gestures (such as appropriation, combination, and assemblage), this worldly dimension is redeemed in an openly humanistic manner: “Generally, it is the people, the subjects that are lacking in what I do – the artist explains – I’m talking to you about them, but they’re not there. It’s as if I were using the feeling of loss as material.”4 The most illuminating example of this attitude is provided by the pair of lamps that constitute Untitled (2021): one, connected to the electrical outlet, is on; the other, without power, lights up thanks to the reflection from its partner. Although starting from an asymmetrical, even opposite, condition, a communion is achieved through the metaphor of the luminous kiss.

Thingness – apparently obtuse – seems to dominate two blankets, different in size and workmanship but similar in color, folded and placed on the ground. Their thingly character, which would make them indistinguishable from normal everyday objects, is however denied by the title: In the first blanket, the lengthy title reads, In Alvorada, in Brazil, Vera Junqueira wove wool yarn the color of night and the same length as the distance from the earth to above the weather; the second title is In Turin, Cristina Donato wove merino wool yarn that is the color of night, and a length equaling the distance from the earth to above the weather. Part of a series, the two blankets share the same weaving process, involving the use of different types of yarn whose length is equal to the distance between the earth and the troposphere, the space beyond which meteorological time (invoked in the title) does not exist. Through this textual device, characteristic of conceptual art, the viewer mentally accesses a space that would otherwise only be experienced in aerial flight, a layer of meaning that projects the artifact beyond its materiality. Another major thread woven into this series has to do with human agency. Employing yet another conceptual topos, the realization of the work is delegated to a weaver. “Things do not exist without being full of people,”5 recalls Bruno Latour. Here the object reveals its humanness by declaring the process of execution, by a person identified by name and surname.

The interpretative key contained in these titles becomes more enigmatic in the case of the owl (Diamond inside an owl). Here, the title asserts that a diamond is hidden inside the stuffed animal: this, however, is invisible to the viewer, as is the content of the cardboard box on which the bird rests (it is the collector’s privilege to be able to open it and discover the sheet and pillow that the author has set inside). Here it’s the taxidermy process that reduces a living being to the state of a thing. Death, observes Michael Taussig reflecting upon Sylvia Plath’s poems, seems to have the ability to transform people into objects and at the same time to bring inanimate objects back to life.6 The bird of prey seems to have remained perched in this double transmutation: it also contains something precious but accessible only by means of thought: “Sculpture is one of the really rare places in the world where you can start to describe certain things that you can’t access specifically,”7 says Dodge.

The same materialistic vitalism inhabits Giovanni Termini’s sculpture. Firmly located in a space that projects itself into the temporal dimension, open to the process that dictates the materials, Termini’s work is nourished – as the author states – “precisely by the conflicts that it tries, in vain, to quell.” Indeed, “I don’t see any other stimuli for research,”8 he concludes.

This agonistic tension is made explicit starting from the title of the work, which affirms the notion of art as a stumbling block, impediment, hindrance (Obstacles, 2019). The installation indeed aligns a series of obstacles: a cordoned bollard, a road bump, a pole supported by a pair of tripods, a structure of scaffolding pipes, a beam, a barrier. The sequence is unified by a uniform light blue paint. Born from the encounter with a museum device, the work extends the initial spurt of institutional critique to a broader consideration of the relationship between the artwork and the viewer, a crucial issue in contemporary art. From the emblematic Duchampian readymade – a coat hanger fixed to the floor that turns into a stumbling block for the artist and therefore the viewer (Trébuchet, 1917) – the artwork seems to describe a genealogy of the fall.9 Heir to this (apparently) ruinous tradition, Termini elevates it to a paroxysm through the multiplication and variation of obstructions. The athletic path, however, chromatically alienated, is engaged as productive: the obstacle is the redefinition of a trajectory, the discovery of unexpected possibilities, a generative act.

Obstacles reaffirms the thingly quality that characterizes the sculptor’s work from the beginning. As Marco Bazzini points out: “Termini does not introduce into his works objects made by himself manually or in any other artisanal way. No body, therefore, appears foreign or incongruous with respect to the characteristics of the materials available on the market that give rise to its conformations. In his sculptures, the quality of the objects maintains an objective criterion (in the proper sense of an identity of the object).”10 This objective posture, however, is contradicted by an anthropomorphizing that is sometimes transparent in the titles of his works, which betray an emotional investment. Termini’s sculptures are In attesa (Waiting), Necessariamente tesa (Necessarily tense), Momentaneamente aperta (Momentarily open), Disarmata da se stessa (Disarmed by itself), Stretta all’angolo (Cornered), Pregressa (Previous), Delimitata (Delimitated), Riversa (Reversed). Thus, the second work on display is also Inclinata (Tilted, 2009). Here nine morali – wooden joists used in the construction of wooden roofs – are joined in rows of three and held together by an American red adhesive tape. On the top of eight of the morali there is a cube made of Carrara marble; the ninth morale is instead simply painted white (the difference is betrayed by its lack of orthogonality). The whole structure is placed, inclined, on the wall. This state of transience suggests a sense of temporary abandonment, however organized for a possible restart. A moment of equilibrium that, in the multiplicity of elements cohesive with each other, could open up to a social metaphor.

Following the double trajectory of these artists in parallel, Thing Theory entered a second phase at the beginning of the 2010s, punctuated by multiple motifs: the decentralization of the subject, object-oriented ontology, ecocriticism, and posthumanism. Among these, the “political ecology of things” traced by the political theorist Jane Bennett postulates the existence of a “vital materiality” that inhabits both animate and inanimate bodies.11 If her invitation is aimed at recognizing non-human forces as active agents in history, art has long exhibited the vitality of matter, and the work of Dodge and Termini bears witness to this. The artists seem to reclaim that “destiny of objects” which Baudrillard lamented as neglected, reduced to poverty at the expense of the “splendor of the subject.”12

“And here the most solid things escape the imprisonment of one’s own volume, the most common ones disrobe the worn-out clothes of the familiar. Suddenly naked, things discover themselves. The tiniest things become the germs of whole worlds. An object can thus be the pole of a meditation on the universe. As philosophers say, each object can become an ‘opening to the world.’”13 (Gaston Bachelard)

September 2022

1. Bill Brown, “Thing Theory”, in Critical Inquiry 28, no. 1 Things, (Autumn, 2001), p.4.

2. Jason Dodge, artist statement, in https://caseykaplangallery.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/JDPress-Kit.e.pdf.

3. Collezione Maramotti – Jason Dodge A permanently open window, in https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1i5UtYZJ39o.

4. Jason Dodge, artist statement, in https://caseykaplangallery.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/JDPress-Kit.e.pdf.

5. Bruno Latour, “The Berlin Key or How to Do Words with Things”, trans. Lydia Davis, in Matter, Materiality, and Modern Culture, ed. P. M. Graves-Brown (London, New York: Routledge, 2000), pp.10, 20.

6. Michael Taussig, “Dying Is an Art, Like Everything Else”, in Critical Inquiry 28, no. 1 Things, (Autumn, 2001), pp.305-316.

7. Collezione Maramotti – Jason Dodge.

8. Giovanni Termini, unpublished statement.

9. This genealogy is reconstructed by Alberto Zanchetta in Giovanni Termini e Alberto Zanchetta, Quella cosa su cui inciampi (la c., 2020).

10. Marco Bazzini, “Quando il cantiere diventa forma”, in Giovanni Termini (Prato: Gli Ori, 2021), p.140.

11. Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter. A political ecology of things (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010).

12. Jean Baudrillard, Fatal strategies, trans. Philip Beitchman and W. G. J. Niesluchoski, ed. Jim Fleming (New York, 1990), p.111.

13. Gaston Bachelard, Il diritto di sognare, trans. Marina Bianchi (Bari: Edizioni Dedalo, 1975), p.155.