«L’attesa non è tempo sprecato». Partiamo da questa riflessione sul tempo. La troviamo in apertura di una recente pubblicazione – un libro d’artista in 120 copie – che Simone Berti ha realizzato per la prima edizione di un programma di residenze avviato dall’antica tenuta vinicola San Leonardo, con la cura di Giovanna Amadasi.

Prima ancora di addentrarsi tra le pagine, gli scenari che si aprono all’immaginazione a partire dal titolo spaziano tra percorsi differenti. La frase rimanda a una saggezza contadina, ma dentro possiamo trovarci i riflessi della sapienza orientale o di certo pensiero tecnocritico occidentale. I riferimenti e le suggestioni dunque si rincorrono. Prendendo a prestito la lente di Roland Barthes, potremmo anche intenderla nella logica del discorso amoroso, allora l’attesa diventerebbe sinonimo dell’essenza dell’amore e potrebbe svincolarsi dal suo oggetto, assumendo semplicemente lo statuto di “incantamento”.

L’attesa può ispessire il tempo, rafforzarne la percezione. Sembra quasi che già solo evocandola Berti possa sfidare l’entropia e ribaltare assunti consolidati purtroppo da decenni. D’altronde, nel mondo che egli disegna e ridisegna fin dagli esordi, le relazioni logiche tra le parti vengono spesso sovvertite, e il fatto che questo accada in modo lieve, o talvolta giocoso, non significa che non contempli una poetica radicalità, che non implichi questioni anche spinose.

Fra le condizioni messe in campo dall’attesa incontriamo la lentezza. Rivendicarla come modus non rappresenta un fatto nuovo, tutt’altro, eppure è evidente come per acquisirla a livello profondo, e quindi trasformativo, vada superato quel moralismo produttivista che ancora permea il nostro ormai scarno bagaglio valoriale, un moralismo che continua a improntare il tempo dell’esistenza, quando si lavora e quando ci si svaga. Evocare l’attesa è tutt’altro che una deriva retorica o un’istanza oleografica. Io lo leggo come un assunto politico.

Simone Berti fa parte di quella generazione di artisti che nella seconda metà degli anni Novanta riportò all’attenzione dell’Italia una sensibilità che veniva dalla provincia. Lo ha ricordato recentemente anche Luca Cerizza nel testo che ha accompagnato la personale Soprattutto Alberi alla galleria Schiavo Zoppelli.1 Un fenomeno che mi piace rileggere all’insegna di quanto sosteneva Pasolini quando individuava nella dimensione della provincia, ancora intrisa di cultura contadina, il volto più autentico del paese e ne lamentava la sparizione sotto la pressione omologatrice dell’inurbamento selvaggio e della cattiva gestione dei processi di accelerazione industriale.

A riguardarli oggi, Simone Berti, Diego Perrone, Stefania Galegati, Giuseppe Gabellone, che con narrative divertite si muovevano tra high e low technologies e mescolavano memorie cinematografiche, aie padane, mood cavallereschi, stupori rurali e miti metropolitani, effettivamente stavano forzando lo schema imperante di un capitalismo che inaugurava la sua fase più feroce. Pensarli, come è stato fatto in modo più o meno esplicito, all’interno di una filogenesi poverista, che in parte c’è anche stata, non giova a comprendere il significato della loro presenza in quel passaggio di secolo e di millennio, non aiuta a individuare il valore di quella temporalità estesa e di quella visionarietà ludica con cui, seppure in modo scanzonato, di fatto minavano le strutture di pensiero di un neoliberismo rampante. Così come oggi non gioverebbe alla lettura del lavoro di Berti l’appiattirlo meccanicamente sulle ansie apocalittiche che affannano l’attualità, sebbene in molte sue riflessioni sulla natura possiamo ravvisarne alcuni echi. Interessarsi alle ricerche di Stefano Mancuso sui comportamenti del mondo vegetale o condividere con Leonardo Caffo una posizione antispecista estesa a tutte le forme del vivente non circoscrive, e soprattutto non esaurisce il suo pensiero.

La centralità di un pensiero sulla natura gli appartiene infatti da molto prima che diventasse una diffusa questione di militanza ecologista. Appartiene alla sua storia personale, al suo essere cresciuto tra i boschi del Polesine, dentro un orizzonte agricolo che nel rapporto con la natura comprende tradizionalmente la dimensione esperienziale del lavoro, quella magico-rituale legata ai cicli generativi e quella contemplativa derivante da uno specifico tempo dello sguardo.

Nel percorso di Berti, nel suo girovagare tra forme plastico-performative, immagini in movimento, disegni, grandi quadri dagli spessi telai, collage digitali, dispositivi elettrici artigianali (penso a quelle enormi lampade-scultura che illuminavano i lavori esposti al MACRO qualche anno fa), uno dei tratti che mi sembra ricorrente, una sorta di invariante – per dirla con Bruno Zevi –, che da metodologia operativa si fa metalinguaggio e sostanza concettuale e da lì postura etica, è la coltivazione della libertà. Una illimitata libertà di reimmaginare il mondo, di esplorarlo secondo percorsi fisici e approfondimenti disciplinari, di riconfigurarlo assecondando un’urgenza esistenziale che via via, nel corso del tempo, si è andata definendo come una forma di resistenza. Al di fuori delle piazze organizzate, sganciata dagli slogan di tendenza, ma non per questo meno significativa e meno tenace.

La ritroviamo anche nella costruzione di questo piccolo oggetto editoriale per il programma Arte a San Leonardo, dove disegno, fotografia e tecniche digitali distillano un’esperienza intima e immersiva nella natura e dentro i luoghi e i tempi dei processi di vinificazione, in un contesto che offre uno stratificarsi di significati e di memorie da poter accogliere e destrutturare, per poi ricostruire e in parte risignificare. Dall’essere bosco all’essere vigneto, dalle impalcature vegetali alle architetture storiche, dalle geometrie orografiche agli schemi araldici, dall’operosità degli insetti al lavoro dei contadini, dagli abitanti della casa alle piante alle rocce al cielo, tutto viene letto da una particolare angolazione che fa della visionarietà uno strumento coesivo e trasformativo, capace di tenere insieme due valori solo apparentemente inconciliabili, la cura e il selvatico.

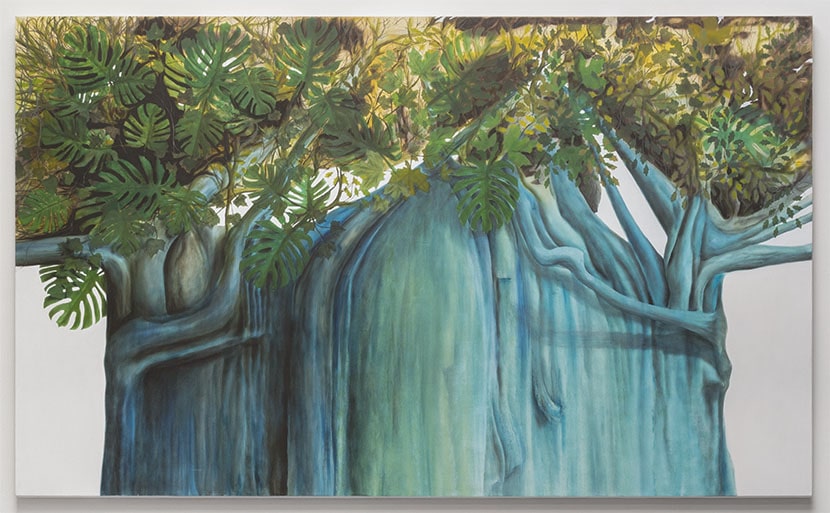

Scorrendo queste pagine, ma anche andando con la mente alle Arboree Volanti, o alla “foresta” di dipinti di alberi iniziata nei primi anni Duemila, veniamo coinvolti da un metamorfismo sprigionato dalla natura che diventa tutt’uno con quello che l’artista a sua volta proietta sulla natura stessa, e poi sugli oggetti, sui macchinari, sulle architetture, sul paesaggio. Un gioco complesso di camouflage e ribaltamenti che attraverso la tattica del depistaggio conduce a una visione spiazzante, come nella letteratura fantascientifica di cui si è sempre nutrito, come negli arredi domestici sospesi in aria da cui rifletteva sul senso della gravità, come nelle costruzioni fantastiche con le quali ha abbigliato le teste di leggiadre gentildonne affioranti dal passato. C’è una nuova (o molto antica) forma di coesistenza nei suoi lavori che sembra fronteggiare l’atomismo individualistico in cui ci siamo tutti ritrovati ad esistere. È vero, i suoi soggetti sono spesso isolati, stagliati contro un fondo bianco che monumentalizza la loro solitudine. Ma credo che quello abbia a che fare con la necessità di confrontarsi senza filtri con elementi archetipali, un risalire alle origini per un nuovo interrogarsi.

Ci sono due passaggi di Savinio che mi sembrano calzanti per il ragionamento fin qui svolto. Uno, sintetico ma particolarmente denso, si riferisce a quando, prendendo le distanze da certi schematismi surrealisti nell’approccio alla dimensione onirica, insisteva sulla necessità non tanto di indagare i sogni quanto piuttosto di «farsi uomo che sogna»2; l’altro, che collego al primo, riguarda le ragioni e i modi dell’arte: è per colpa del «troppo attenersi alla inesistente realtà che la pittura è la meno filosofica delle arti».3 Come a dire, è prendendo le distanze da quella che solo in apparenza ci appare come realtà, è solo in una presunta condizione di irrealtà che è possibile restituire all’arte il respiro della filosofia.

Torniamo dunque al camouflage e al suo ambiguare la realtà. In un saggio intitolato “Semiotica e camouflage”, partendo dalle opinioni ancora discordanti sull’etimologia della parola, Paolo Fabbri scriveva: «Il camouflage sarebbe un incanto gettato sulle cose, perché abbiano un senso diverso da quello consueto. È l’equivalente dell’inglese to get a spell, “gettare un incanto”. Trovo suggestivo che camouflage abbia la stessa radice di carmen, poesia».4 Camouflage, incanto e poesia ci vengono prospettati su un terreno di reciprocità.

Scorrendo il testo, dopo una puntuale lettura dell’uso di questa naturale strategia difensiva all’interno della logica preda/predatore che struttura il mondo animale e quello vegetale, e dopo una riflessione su come gli artisti lo abbiano variamente utilizzato in relazione ai grandi conflitti novecenteschi, c’è un punto in cui il semiologo accenna al suo utilizzo odierno sul fronte dell’arte: «Gli artisti contemporanei, eticamente ed esteticamente più acuti, mettono spesso a fuoco il camouflage. Ne usano la qualità eristica – la retorica del conflitto – per sottolineare ironicamente una caratteristica delle società attuali, che non sono più società della repressione, ma del controllo […]».5

Non credo siano necessarie ulteriori parole.

Simone Berti ricorda, sogna, camuffa, depista, progetta, trasforma. Ecco, credo che l’attesa sia esattamente il tempo necessario alla trasformazione.

Arte e Critica, n. 97-98, primavera – estate 2023, pp. 42-47.

1. Simone Berti. Soprattutto Alberi, testo di Luca Cerizza, Schiavo Zoppelli Gallery, Milano, 11 febbraio – 19 marzo 2022.

2. S. Cirillo, Alberto Savinio. Le molte facce di un artista di genio, Bruno Mondadori, Milano 1997, p. 166.

3. A. Savinio, Nuova enciclopedia, Adelphi, Milano 1977, p. 317.

4. P. Fabbri, “Semiotica e camouflage”, in AA. VV., Falso e falsi. Prospettive teoriche e proposte di analisi, a cura di Luisa Scalabroni, Edizioni ETS, Pisa 2011, pp. 11-25. (Consultato su: https://www.paolofabbri.it/saggi/semiotica-e-camouflage/)

5. Ibidem.

TO MAKE HIMSELF A MAN WHO DREAMS

“Waiting is never time wasted.” We begin with this reflection on time. It appears at the outset of a recent publication – an artist’s book in 120 copies – produced by Simone Berti for the first instalment of a residency programme initiated by the venerable San Leonardo wine estate and curated by Giovanna Amadasi.

Even before delving into its pages, scenarios unfold in one’s imagination from the title onward, radiating out along separate paths. The phrase harks back to an old peasant saw, but in it we might note the ripples of oriental wisdom or certain western technocritical thought. Just so, such references and suggestions chase each other in circles. If we were to look through Roland Barthes’ lens, we could also understand it by the logic of the lover’s discourse, whereby waiting would become synonymous with the essence of love and could disentangle itself from its object, simply assuming the status of ‘enchantment’.

Waiting can congeal time, redouble our perception of it. It almost seems as though, merely by evoking it, Berti can defy entropy and invert assumptions that, unfortunately, have consolidated for decades. In this world that he has drafted and re-drafted from the start, meanwhile, the logical relationships between its parts are often subverted. Nor does this subversion’s light touch or its sometimes playful manner preclude a poetic radicalism, nor the addressing of even thorny issues.

Among the states brought into effect through waiting, one is slowness. Claiming it as a modus is not a novelty – anything but – yet it is evident how, in order to enter it at a profound and therefore transformative level, we have to overcome the productivist moralism that still permeates our now-meagre assortment of values, a moralism that continues to mark the duration of our existence, our allotted time for work and our allotted time for amusement. To evoke the act of waiting is anything but a rhetorical meandering or a crudely veristic impulse. I read it as a political position.

Simone Berti belongs to that generation of artists who in the late 1990s called a regional sensibility back to Italian attention, as Luca Cerizza recently recalled in his text accompanying Berti’s solo exhibition Soprattutto Alberi at the Schiavo Zoppelli Gallery.1 I prefer to reinterpret the same phenomenon in the spirit of Pasolini’s statement identifying Italy’s provincial dimension, still steeped in peasant culture, as the nation’s most authentic face, lamenting its disappearance under the homogenising pressure of runaway urbanisation and the mismanaged processes of industrial escalation.

Looking back at them today, Simone Berti, Diego Perrone, Stefania Galegati and Giuseppe Gabellone – whose amused narratives skipped between ‘high’ and ‘low’ technologies, blending cinematic memories, Po Valley farmyards, overtones of chivalry, rural astonishments and metropolitan myths – effectively forced the hand of the prevailing capitalist pattern as it entered its most ferocious phase. To frame them, as some more or less explicitly have, within Arte Povera’s line of descent (a lineage that to some extent exists) does not help us understand the meaning of their emergence at the turn of the century and the millennium, nor does it help us evaluate that distended temporality and visionary playfulness with which, albeit blithely, they in fact undermined the thought structures of rampant neoliberalism. In the same way, it would not aid current interpretation of Berti’s work to mechanically iron it onto the apocalyptic anxieties that plague current affairs, even if we can discern some echo of them in many of his reflections on nature. His interest in Stefano Mancuso’s research on plant-world behaviour or his sharing of Leonardo Caffo’s anti-speciesist position, which extends to all forms of life, does not circumscribe and above all does not exhaust his thought.

In fact, his was an ecocentric intellect long before such thought became a widespread question of ecological militancy. It belongs to his personal history, to his having been raised in the woods of Polesine, within an agricultural landscape whose relationship with nature traditionally embraces the experiential dimension of work, a magical-ritual dimension bound to generative cycles and a contemplative dimension deriving from the specific tempo of one’s gaze.

Throughout Berti’s journey, in his wanderings among sculptural-performative forms, images in movement, drawings, sprawling paintings on deep stretchers, digital collages and handcrafted electric appliances (here I am thinking of the enormous lamp-sculptures illuminating the works he exhibited at MACRO a few years back), a recurring trait that I believe I see is the cultivation of freedom, a sort of ‘invariant’ – as Bruno Zevi put it – that extends a working methodology into metalanguage, into conceptual substance and, from there, into an ethical position. His is an unlimited freedom to re-imagine the world, to explore it through physical pathways and disciplinary investigations, to reconfigure it by indulging an existential impulse that over time has gradually asserted itself as a form of resistance. Outside prefabricated standpoints, emancipated from trendy slogans, but no less meaningful or tenacious for it.

The same freedom has manifested itself in the construction of this little object published for the Arte a San Leonardo programme, in which drawing, photography and digital techniques distil an intimate and immersive experience of nature and of the environments and tempi of the winemaking process: a context permitting a stratification of meanings and of memories that can be absorbed and deconstructed, then reconstructed and partially re-signified. From forest to vineyard, from terraces of vegetation to historical architecture, from orographic geometries to heraldic patterns, from the exertions of insects to peasant labour, from house-dwellers to plants to rocks to sky, all is interpreted from a particular perspective that turns the visionary sensibility into a cohesive and transformative tool equipped to unite two only apparently irreconcilable values: nurture and the wild.

Leafing through these pages, but also mentally returning to the Arboree Volanti or to the ‘forest’ of arboreal paintings begun in the early 2000s, we are inducted into a nature-spawned metamorphism ultimately indivisible from what the artist in turn projects onto nature itself and onto objects, machinery, architecture and the landscape. A complex game of camouflage and inversions that, through tactical misdirection, leads to a disorienting vision akin to the science-fiction novels that he has always devoured, akin to the levitating domestic furnishings by which he has reflected on the meaning of gravity, akin to the fantastic constructions with which he has decorated the heads of graceful ladies resurfaced from the past. There is a new (or ancient) form of coexistence in his works that seems to confront the individualistic atomism in which we all find ourselves entrapped. True, his subjects are often isolated, silhouetted against white backgrounds that monumentalise their solitude. But that, I think, has to do with his need for an unfiltered engagement with archetypal elements, for a seeking back to the beginning to kindle new inquiry.

There are two passages from Savinio that seem fitting in light of the reasoning thus far outlined. One, concise but particularly dense, refers to the moment when, distancing himself from certain Surrealist schematisms in his contemplation of an oneiric dimension, he insisted on the need not to investigate dreams as much as to “make himself a man who dreams.”2 The second, which I associate with the first, concerns the reasoning and modes of art: it is by fault of “too close an adherence to non-existent reality that painting is the least philosophical of the arts.”3 As if to say that it is only by distancing ourselves from what merely appears to us as reality – only through a putative state of unreality – that we can restore philosophical breadth to art.

To return, then, to camouflage and its confusions of reality: in an essay entitled ‘Semiotica e camouflage’, setting out from still-discordant opinions on the word’s etymology, Paolo Fabbri wrote: “Camouflage would seem to be an enchantment upon things that lends them a meaning other than their habitual one. It is the equivalent of the English ‘to cast a spell’, gettare un incanto. I find it suggestive that camouflage has the same root as carmen, poetry.”4 Camouflage, enchantment and poetry appear before us on interdependent terms.

Scanning Fabbri’s text, after his adroit reading of this natural defensive strategy’s function within the prey/predator relationship that structures plant and animal worlds, then after a reflection on the varied use that artists have made of it in relation to the great twentieth-century conflicts, at a certain point the semiologist refers to its use today along the battle lines of art: “Contemporary artists, ethically and aesthetically more astute, often focus on camouflage. They use its eristic quality – its rhetoric of conflict – to ironically emphasise a characteristic of today’s societies, which are no longer societies of repression but of control.”5

I think no further words are necessary.

Simone Berti recollects, dreams, disguises, wrong-foots, transforms. Just so, I believe that waiting consists precisely of the time that transformation requires.

Arte e Critica, no. 97-98, Spring – Summer 2023, 42-47.

1. Luca Cerizza, Simone Berti: Soprattutto Alberi, text accompanying the exhibition of the same name at Schiavo Zoppelli Gallery, Milan, 11 February – 19 March 2022.

2. Silvana Cirillo, Alberto Savinio: Le molte facce di un artista di genio (Milan: Bruno Mondadori, 1997), p. 166.

3. Alberto Savinio, Nuova enciclopedia (Milan: Adelphi, 1977), p. 317.

4. Paolo Fabbri, ‘Semiotica e camouflage’, in Falso e falsi: Prospettive teoriche e proposte di analisi, ed. by Luisa Scalabroni (Pisa: Edizioni ETS, 2011), pp. 11-25. Accessed 12 June 2023, https://www.paolofabbri.it/saggi/semiotica-e-camouflage/

5. Ibid.